Places of residence have adored artworks as far back as the date goes. Whether it be the caves where the earliest communities chalked stylized bi

Places of residence have adored artworks as far back as the date goes. Whether it be the caves where the earliest communities chalked stylized bison representations on the rock walls for ceremonial purposes for a successful hunt or the Flanders in the Early Renaissance to incorporate the figures of revered deities in a domesticated setting for attaining affinity which wasn’t procured on a packed Sunday mass. In more recent times, our homes have become an extended space for the collection of artworks. Free from the political and colonial history baggage that museums bear, domiciliary artworks carry within the possessions of a collective memory of the occupants. A presentable photograph of a late family member in the hall represents an abstract as well as an esoteric of the memory of the loved one for the residents of the house. The visitors need not know the jubilance of the figure in the portrait which death has taken away in all its seriousness, still echoes in the hearts of those who were aware of it.

Similarly, the theme of hope that still flickers amidst darkness was underscored in the recent exhibition of Lahore’s Lakir Art Gallery, which in accordance with the argument at hand, utilizes a residence as an extended space for showcasing art. Whispers in the Dust, curated by artist Fatima Butt of the collective Humsar, exhibited the works of six creative practitioners across the country to explore their interpretations of hope and solace in times of loss and despair. The curatorial premise was set under the tone of current atrocities that are being perpetrated upon humanity, especially in the context of Palestine, Kashmir and Pakistan.

Amna Yaseen’s highly saturated photographs depicted the transformative angle of the vandalization of several churches and Christian residents of Jaranwala, Punjab after the riots of August 16th, 2023 on the allegations of the desecration of the Quran by the hands of the minorities. One-half of the diptych of photographs captured one church shrouded in a virescent light while being encircled with emblems of the Islamic faith. Whereas, the other photo revealed a life size cross, detached from its context, has been placed in what seems like an open courtyard or Sehan behind a local mortuary bed. Fuschia is an understatement as compared to the imminent threat imposed by far-right extremist groups of Pakistan to its Christian minorities. It is a cross they have to bear that no amount of white, whether on-fourth or whole, can ever compensate.

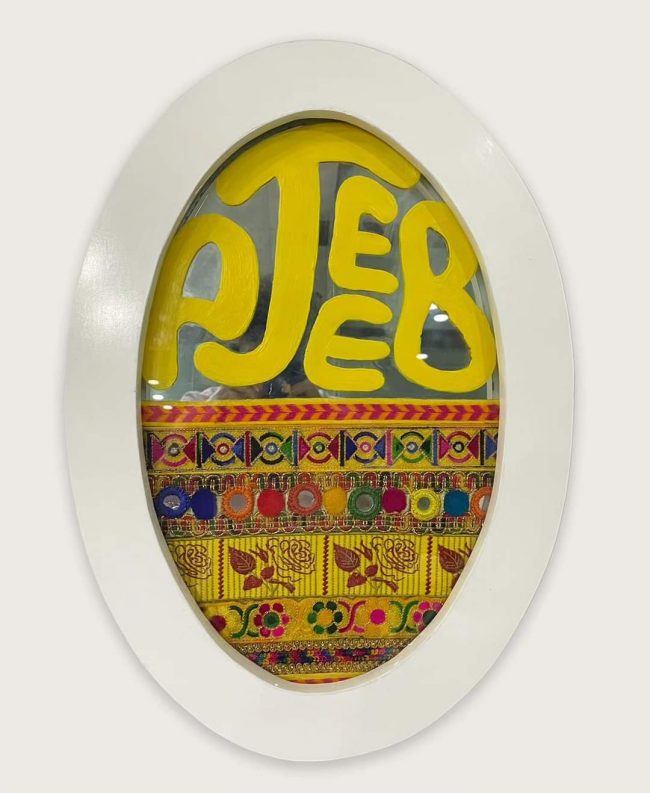

Amina Jameel’s multilayered works depict the alternative nature between fiction and non-fiction. She creates veneers of line drawings on top of each other on handmade sheets until all images lose their meaning and share a collective pool of existence. Her work comments on the expendability of housemaids to an extent of obscurity yet remains the central focus of her artworks. Whereas, Areeb Tariq deployed gaudy tapestries with banal objects to highlight our post-colonial identity and the dimming splendor of our traditions and locality owing to the expansion of the cityscape.

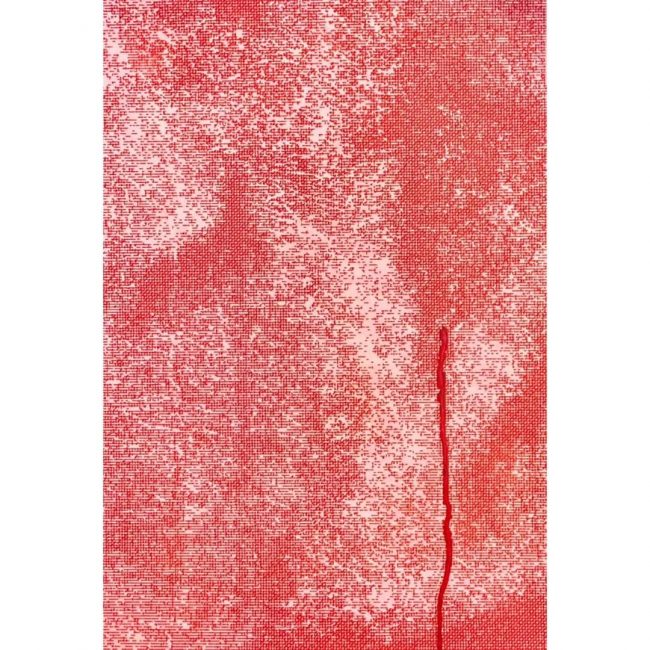

Malika Batool carefully peels the layers off her figures of interest from the encroaching darkness by illuminating them with a hazy effect. Her fundamental concept revolves around nature as it is the foremost inspiration of her work, whether it’s humanistic or bestiary. Batool’s paintings depict the despair that we tend to mask in order to blend in, which inevitably reveals itself as all things do over time. The emergence of undefined pixels into calligraphic text becomes visible in Qasim Bugti’s drawings as they fall on the canvas in vertical movements. The placements of his picture elements mimic the micro view of broken digital screens in scarlet tones. Sadqain’s life-size installations were executed in white plaster with the amalgamation of black ink which was slowly absorbed by the casts to give it the attribute of aging over time. The two adjacent reclining chairs had a narrow wooden stool placed between them, which hosted plaster plates positioned on top of each other in a haphazard fashion was a scene out of the Mad Hatter’s Tea Party. Ink-soaked teapot and a cup were set down on either chair and seemed to be conversing in a language that only his other crockery pieces could decipher. The universal idea of purity is of significance here; any white-bleached object is at risk of being tarnished when exposed to the external environment.

COMMENTS