Beautiful Nightmares, a solo show by Mariam Agha, was exemplary in it’s production of a cultural object with all the hallmarks of a consequential eve

Beautiful Nightmares, a solo show by Mariam Agha, was exemplary in it’s production of a cultural object with all the hallmarks of a consequential event.

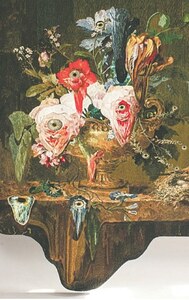

Marium Agha’s exhibition, titled “Beautiful Nightmares” was a highly involved project curated and staged by Scheherazade Junejo. In fact both the written poetic presentations of the artist, on one hand, and the curatorial statement on the other, seemed to have developed in perfect harmony and symmetry . The works were factually re-worked floral tapestries, but this appropriation was not superficial, by any means: the works not only retained their original complexity of design and colour, but, by a feat of painterly imagination combined with the painstaking craft of embroidery, transformed the original in order to powerfully express Agha’s intentions.

Parts of the curatorial statement are best reproduced here, since the narrative essentials were put forward with much consideration and precision:

“Marium Agha delves into the complexities of the female experience, juxtaposing seduction with disturbance, permanence with change, and the sacred with the profane. In her exploration of love and its manifestations, particularly in her latest series, Agha confronts the dichotomy between fairytales and life lessons, challenging perceptions and realities associated with the female state.” Also, “ Agha’s tapestries resonate with intergenerational knowledge and experiences, prompting a reevaluation of established narratives. Her work exposes the constructed nature of historical ideals and cultures surrounding love, revealing the reality that lies beneath. By deconstructing the archive of floral, feminine imagery, Agha challenges the notion that femininity has been written based on supposed ideals rather than truth. The relentless evolution of sensibilities over time, shaped by societal expectations, is a central theme in Agha’s exploration, ultimately seeking to excavate the underlying reality beneath the layers of constructed narratives”

At the descriptive level, Agha’s oeuvre continues the fascination that the artist has with fabric and thread, and indeed, her idiosyncratic and highly iconoclastic style has been channeled into what, in Junejo’s reckoning, appears to be a “darker territory” than much of the previous works. During an extended conversation with the artist, Agha articulated the shift, as being, in just so many words, a moving away from a relatively explorative and experimental ethos to one that, as it transpired, was deeply existential in tone, and further, by way of contemporary analytical discourse, a thoroughly actantial project in which the works are completely configurative of the artist and her experiential domain, as it were. While it may not be out of place to say that the imagery Agha had produced was related to the Dalinian treatment of the horrors of bodily experience, there were close affiliations with Julia Kristeva’s account of the terrifying emotional narratives produced in the innermost recesses of the female psyche, by the confabulation of time and reality. However, it can be safely said that Agha seemed to have displayed notable determination in this gladiatorial arena and had come out of the fight the undisputed victor.

In order to speak fully of Marium Agha’s ethos, it would be worthwhile to engage with the slightly esoteric worlds of semiotics and linguistics, since there are some aspectual considerations, not only in Agha’s work, but in this emergence of an overall project involving artist and curator, a scenario that is intrinsically interconnected with a number of issues that can be brought into focus through a degree of conceptual thought.

Verb tenses in language are initially organized in a way that relates to the difference between conversation and storytelling. Unlike the traditional view that focuses on the speaker’s relation to what they’re saying, here – situationally – the emphasis lies on how people in a conversation guide the understanding of the message. The shared understanding between people talking also influences the structure of language itself. Therefore, the distinction between a “narrated world” (telling a story) and a “commented world” (discussing or explaining) is foregrounded. This approach helps separate verb tenses from the constraints of real-time and allows for observations of verb tenses in storytelling. Specifically, past and imperfect tenses are considered “narrative tenses” not just because they describe past events, but because they convey a sense of detachment or relaxed attitude towards the events being talked about.

While Paul Ricoeur himself doesn’t directly mention the gestuality such as that proposed by Greimas, we can draw connections based on their shared focus on linguistic structures and communication. Greimas was known for his semiotic theory, which includes the analysis of gestures as a form of communication. In the present context of speaking about Mariam Agha’s works, the discussion about the organization of verb tenses in language reflects how communication is structured therein, the framework which she constructs whereby gestures are considered as part of the larger discursive system (which, of course, includes both verbal and non-verbal elements). In other words, in Agha’s system, with remarkable fidelity, the organization of tenses in relation to discourse and narrative, experienced time and the individual as an element of a social grouping, touches upon how language is used to convey messages. In this context, gestuality, or non-verbal communication through gestures, could be seen as an additional layer that complements and interacts with the otherwise verbal communicative components

How does this bear with our present explanation? Agha is engaged in a process – that of the “relation of interlocution” and the “guidance of the reception of the message,” which implies a dynamic interaction between speakers. This interaction involves not only the words spoken but also potentially includes gestures, expressions, and other non-verbal cues, as we have noted above. It follows that the concept of gestuality can, with confidence, be extended to include artistic projects. When it comes to art, particularly visual art, the creation and interpretation of visual elements can be seen as a form of gestuality. Quite simply, artistic visuality involves the genetive meanings and emotions. Artists use visual elements to communicate ideas, tell stories, or express abstract concepts. Viewers, in turn, interpret and respond to these visual cues, creating a dynamic and non-verbal exchange of meaning. This play of utterance and interpretation often involves a shared cultural and social context, making visual art a form of communication that goes beyond language -the interaction between the artist and the viewer becomes a non-verbal dialogue facilitated by the gestuality of artistic visuality, that itself is ultimately responsible for the production of a cultural object. In a form of circularity, essentially, the use of these objects involves specific gestures or actions, and they can serve as tools or substitutes for individuals. These objects can take on new roles in different cultural contexts, functional roles inasmuch that they can be used in different ways or for different purposes. This adaptability allows for the creation of hierarchies of gestures and practical skills – ways of life or, even, lifestyles – the establishment of cultural dimensions in a society, such as ways of doing things related to not just food and clothing, but to, literally, being who and what one is. These dimensions are described as isotopies, which are like patterns or structures of practical and mythical knowledge and skills within a culture.

We may call the relation between the time of narrating and the narrated time in the narrative itself a “game with time,” this game has as its stakes the temporal experience (Zeiterlebnis) intended by the narrative. The task of poetic morphology is to make apparent the way in which

the quantitative relations of time agree with the qualities of time belonging to life itself. Fundamental time is implied, this time of life is “codetermined” by the relation and the tension between the two times of the narrative and by the “laws of form” that result from them. In this respect, we might be tempted to say that there are as many temporal “experiences” as poets, even as poems. This is indeed the case, and this is why this “experience” can only be intended obliquely through the “temporal armature,” as what this armature is suited to, what it fits.

Marium Agha’s exhibition was true armature – it supports her signatorial ethos within itself of course, but by extension of notions of narrativity, of multiple stories skillfully told as though in an absorbing novel, which in this case is Junejo’s contribution are her curatorial skills, it strongly represented a key development in our art world: certain artistic practices are creating “laws of form” that have such cohesion of curatorial structuration that they constitute meditations and horizons. Finally, in the words of Ricoeur: “It is the handling of the relation of the time of narration to the time of life through narrated time that is important. Here Goethe’s meditation comes to the fore: life in itself does not represent a whole. Nature can produce living things but these are indifferent. Art can produce only dead things, but they are meaningful. Yes, this is the horizon of thinking – drawing narrated time out of indifference by means of the narrative.”

,

Thus, Beautiful nightmares was exemplary in it’s production of a cultural object with all the hallmarks of a consequential event, full of ‘relations and tensions’ that do not allow ‘indifference’. This cultural object is almost surely the standpoint from which it is given to us to see the paradigmatic and extremely problematic assignation of women to a ‘woman’s world’, this “game with time,” a game which has as its stakes the temporal experience of being Woman.

COMMENTS