Archiving, whether personal or official is undeniably the most common means to secure historical knowledge. It is collected, observed and – if needed

Archiving, whether personal or official is undeniably the most common means to secure historical knowledge. It is collected, observed and – if needed – recovered. Many may argue that most mediums in contemporary art are a process of documentation itself; storing fictionalized or real narratives and immortalizing a canon of abstract thoughts and memories in time. However, with the passage of time every living organism as well as inanimate object records its lived history – current or ancient – in and on itself. Canvas Gallery’s latest exhibition “Figuratively Speaking” is a stark evidence of this notion where four emerging artists express themselves on subjects they are sensitively observant towards, while using individual ways to store information which makes one debate whether the process of archiving is a contested subject and medium in itself. The artists congregate on the common theme of not only preserving but representing history – those which are individually experienced, shared or merely embedded in insentient objects.

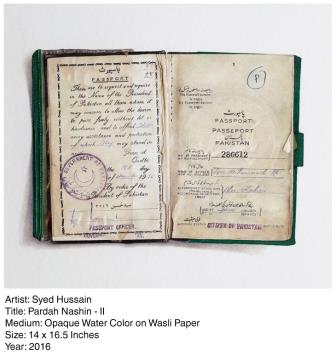

Quetta born Syed Hussain ventures into his personal history to configure his identity which he feels he has barely grasped. Interestingly however, the trajectory in Hussain’s work explores the collected history behind an entire ethnicity. Belonging to the Hazara community, Hussain felt like an outcast wherever he travelled and experienced a disassociation of sort for his distinct physical features and accent. This unjustified demeanour towards him compelled Hussain to backtrack his ancestral life and really question what makes him him – perhaps in an undeterred struggle to weave his isolated self back into the country’s history, thereby proving that he rightfully belongs to and integrates with the land just as anyone else.

In order to do so, Hussain forages for any substantial evidence which verifies the identity of a certain ancestor or their family. Hussain documents as well as excavates his lineage by using stamps, signed notes and vintage photographs. Further incorporating passports and ration cards, he carefully chooses sections to omit and presents an unfinished – possibly a never ending – quest at fully discovering himself. While many portraits glare back with assertion, several have their eyes expunged; oblivious not just to their past but also blinded before their future – our present. The visuals come across as a distorted reflection of the artist, a manifestation of his identity through history.

Following a similar pattern is Veera Rustomji, who recollects her family photographs which chronicle the history it underwent. Having initially focused on the Zoroastrian community she is from, Rustomji’s current work remains personal yet displays a globally shared phenomena. She critiques one’s inherited history and shadows the process of threading one’s ancestry thereby associating them to a time they didn’t exist in – to individuals they never met, and to experiences they never endured.

The unrefined mark making in her paintings expose Rustomji’s frantic attempts at making sense of the disjointed images. The gestural strokes not only echo her violent desire to discover the past, but also evoke a sense of erasure with time and disintegration of what she may or may not relate her present self to. The faces blur and the backgrounds erode until the residue is a vague collection of crude patches, till the context in each image becomes unidentifiable. Like a jigsaw puzzle, Rustomji tries to fit the pieces together yet the distance in between catalyses a sense of unease – one cannot decipher if the images are repelling apart or like two polar magnets, reaching out to the other to conjoin themselves. Rustomji questions the extent to which one should look back; after all where does one stop on the linear time of bygone and disconnect themselves from what lays beyond? Is it absolutely necessary for one to feed a sense of belonging to a very distant past?

Contrastingly, Heraa Khan’s work records the longstanding segregation within our social order which she has been scrutinizing in her hometown of Lahore. She attentively scans the behavioral tendencies which the seemingly elite often project and also captures their activities and interests. Considering the cosmetic lift Lahore is being given and the shift it has rippled in the intrinsic nature of the metropolis – Khan’s paintings are very pertinent to our ambiguous immediate history.

Khan personifies the escalating gentrification the city is witnessing; the perceivably ostentatious middle-aged woman she places in her visuals is caught performing mundane, self gratifying activities. The items she holds or is situated against reek of privilege and wealth. Khan further heightens the opulence by profusely incorporating gold leaf in her paintings. The frail floral prints symbolize the transience behind most delicacies accessible to an affluent lifestyle. Moreover, they trigger one to immediately think of lawn and other textiles – an indication of flippant consumption and extravagant indulgences which satiate one’s gourmandizing appetite.

However, Khan examines the conceivably lonely nature of these individuals and the restrictions they have internalized which curb them from assimilating beyond their haven. Her subject is partly infused in the overlaying pattern in most of her pieces, whereas in some she is entirely concealed within the intricacies. Viewers are led to ponder whether the cocooned women feel trapped in their cliques or are content with where they are – voluntarily hidden and comfortable at being untraceable.

For Umar Nawaz, the materials itself become the primary focus of his narrative as he unearths the ingrained history and the journey they undertake till the point of their presentation. They become wilful actors; active agents within his artistic process which rope viewers in their convoluted connotations. Nawaz anatomizes their physicality as well as their modifiable properties. His sculptures may intentionally obstruct or disrupt a given space; presumably emerging as unstable edifices.

A tall white washed pillar stands erect in one corner of the gallery. Constructed out of iron, a noticeable crack runs all around the looming structure at its base. The sculpture is initially overwhelming to look at, and gradually incites a response of amusement as the piece appears to precariously rest despite the evident fault. The finesse behind his treatment beautifully juxtaposes the jarring structure itself as does its sheer size against the minute crack.

Standing in solitude, the vertical structure not only holds command of the space dedicated to it, but also invites viewers to circumambulate it. This ritual leads one to involuntarily associate an unfathomable significance to the construction. One cannot help but interpret the pile for a skyscraper – a mascot for our city, or even our country. The pillar resonates the continuously evolving skyline of Karachi despite the city’s shortcomings at its roots. Nawaz’ work becomes a poetic documentation of the fragile state of our nation – head held high in defiance of the crumbling foundations it perilously balances on.

The exposition in its entirety takes a turn not only towards the archives and histories, but how it haunts the consequential present we live in today. Through diverse situations, the artists contextualize the role of memory in visual language, stimulating viewers to reminisce personal and collective memories – history we either experienced or witnessed. Moreover one is drawn to speculate the history we hold no familiarity to as well as that which is current and continues to formulate before us, which we commonly overlook. Their persisting interest in history and its effects through time opens a portal onto the recent past as well as that preceding centuries; the destruction of cities, the socio-cultural evolution of communities; and the transmutation processed within a lifeless object. These diverse recounts accumulatively elicit experiences of nostalgia, poignant concern for the present as well as grave apprehensions of the future.

COMMENTS

Hi, yup this piece off writing is reeally fastidious and

I have learned lot of things from it concerning blogging.

thanks.