Carolina Caycedo is a UK-based, Colombian-born interdisciplinary artist whose work engages deeply with environmental and social justice issues Bor

Carolina Caycedo is a UK-based, Colombian-born interdisciplinary artist whose work engages deeply with environmental and social justice issues

Born in 1978 in London to Colombian parents, Caycedo has lived and worked across various continents, which has significantly influenced her perspective on socio-environmental struggles. Her artistic practice, spanning performance, sculpture, photography, video, and public interventions, reflects a commitment to community engagement and activism. Caycedo’s works have been widely exhibited in major international institutions, including the Tate Modern, London; the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). Her practice is grounded in collaborations with grassroots movements, with a particular focus on the resistance against large-scale infrastructure projects and their effects on natural ecosystems and indigenous communities.

Caycedo’s art cross-examines the consequences of neoliberal development and extractive practices, particularly in relation to water rights, territorial displacement, and ecological degradation. Her ongoing project Be Dammed explores the socio-political and environmental impacts of dams on rivers and the communities that rely on them. Caycedo’s approach involves gathering testimonies and stories from affected communities, incorporating these narratives into her visual art practice. By blending research, activism, and aesthetic forms, she creates immersive experiences that challenge viewers to rethink their relationship with nature and question the power dynamics that shape environmental exploitation.

For the Lahore Biennale 03, Caycedo installed an 8 minutes long 2 channel colored HD video, titled, “To Stop Being a Threat and To Become a Promise.”

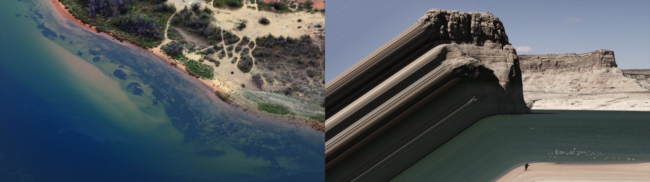

Projected parallel to each other, inside the walls of the British Barracks at the historical Lahore Fort, her work is a profound meditation on the tension between traditional ways of life and the relentless forces of extractivism. The two-channel video work weaves together imagery from various river systems, such as the Colorado, the Yaqui, the Xingu, the Spree, and the Magdalena Rivers, creating a powerful contrast between the ancestral, rural lifestyle and the destructive practices of industrial extraction. By situating these hydrographies side by side, Caycedo invites viewers to consider the divergent ways in which these landscapes are understood and valued—either as sacred territories integral to community life or as mere resources to be exploited.

What makes this piece particularly enthralling is Caycedo’s ability to evoke the spiritual dimension of rivers and landscapes. The ancestral view in the video is depicted through fluid, dreamlike sequences that emphasize the deep, spiritual connection between people and their environment. These scenes communicate a sense of harmony and awe, suggesting that rivers are more than just water; they are living entities, carrying stories, traditions, and the memory of their people. This perspective stands in stark opposition to the mechanized imagery of extractive practices, which appear cold, sterile, and disconnected from the natural rhythms of the earth. The video’s shifts between these contrasting visions are deliberate, making the viewer acutely aware of the stakes involved in the ongoing struggle over territory and resources.

Caycedo’s use of filmic techniques to destabilize the extractive perspective is central to the work’s impact. As the video progresses, the ancestral view exerts a kind of visual and metaphysical pressure on the extractive scenes, causing them to “wobble, shake, unfold, and eventually transform.” This transition suggests the potential for transformation, both in terms of how we perceive nature and in the broader political struggles over land and water. Caycedo’s framing of this shift as a kind of “visual spell” speaks to the power of indigenous worldviews, which challenge the dominance of industrial narratives with their rootedness in reciprocity and spiritual interconnectedness.

The video’s title, To Stop Being a Threat and To Become a Promise, encapsulates this dynamic beautifully. It reflects the ways in which the extractive view sees nature and rural communities as a ‘threat’ to progress and profit, while the ancestral perspective offers an alternative promise—one of coexistence, mutual respect, and sustainable stewardship of the land. Caycedo’s work is a call to imagine a future where indigenous and traditional knowledge can guide humanity toward a more balanced relationship with the natural world, one that respects the integrity and agency of rivers and ecosystems.

What makes Caycedo’s work particularly powerful is her ability to transform activism into a poetic form, where the aesthetic and the political become inseparable. Her installations are more than a critique of environmental destruction; they are a call to action, asking audiences to reconsider their complicity in extractive economies. Through a deep sensitivity to the experiences of the communities she represents, Caycedo’s art raises critical questions about sovereignty, the rights of nature, and the meaning of progress in a time of ecological crisis.

Carolina Caycedo’s artistic practice serves as a fundamental intersection between art, activism, and ecology. Her ability to weave together community stories, research, and striking visual elements creates a profound commentary on the pressing environmental challenges of our time. By engaging directly with communities affected by ecological degradation and displacement, she offers a model of art-making that is both ethically grounded and aesthetically rich. Caycedo’s work pushes the boundaries of what contemporary art can achieve, serving as a reminder of the power of art to inspire awareness, solidarity, and transformative change.