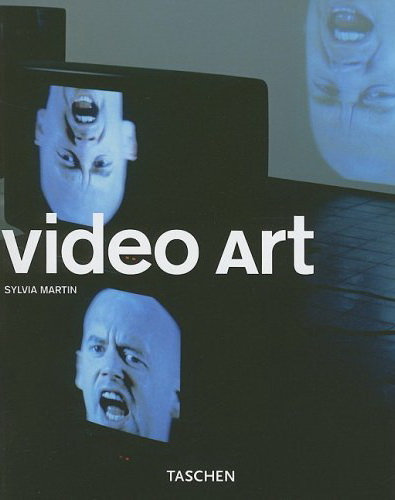

It is always interesting to read of the conception and progression of an art form. In Sylvia Martin’s, Video Art it becomes evident that the genre of

It is always interesting to read of the conception and progression of an art form. In Sylvia Martin’s, Video Art it becomes evident that the genre of video art grew very much out of a particular set of political and social circumstances of the ’60s. In a climate of change, avant-garde art-making was further bolstered by innovation in analogue to digital recording technologies. While video art responded to “anti-war protests [Vietnam], the student movement, feminism, and the liberation movement of black America,” it also became a place of collaborative practice for dancers, writers, musicians and artists in the United States and in Europe. In the new found interdisciplinarity, video artists began to create works in which time, space and the human body became major “thematic emphases” of the artworks.

The popularisation of television also had an effect on the practice of video artists as they sought to separate themselves from TV programming that called for a passive reception of images. Creating non-linear works allowed video artists to fully engage with their medium, themselves and their audiences. In 1969, Vito Acconci created Following Piece in which he followed and recorded people at random in public places in New York City for over 23 days. Along with Andy Warhol, Nam June Paik was an early adopter of portable video and in 1965, made a live video recording of Pope Paul VI’s visit to New York City. In 1998, Richard Billingham’s Fishtank was the product of three years of recording of the daily life of his family. In 2013, Billingham’s work seems to have been a precursor to present-day reality TV. But in an age where we are always electronically connected and able to receive up to the minute details of the royal birth, it is difficult to conceive of Paik’s live recording as once having been ground-breaking.

With video, artists had a chance to become both subject and director of their recordings. They were able to live record themselves, view recordings after the fact, show recordings over split screens or on multiple screens. Performance artists were also interested in the body’s “behaviours when in pain, in danger, or experiencing desire.” In the works of Marina Abramovic and Chris Burden (in SHOOT, a live performance in which a friend fires a weapon at the artist) limits of the physical body were tested. In the ’70s, Bruce Nauman was interested in mechanising the body perhaps in ways similar to Marina Abramovic in her 2010 show, The Artist is Present at the MoMA, NY. Female artists Dara Birnbaum and VALERIE EXPORT also conducted live performances in which people’s attitudes towards women in patriarchal society were recorded.

Along with a history of the Video Artmovement, Martin provides a discussion of key artists of the genre, including Nam June Paik, Bill Viola, Vito Acconci, Martha Rosler and Gillian Wearing, putting their works in context with fellow artists. It is important to remember that the history of video art is tied mostly to the history of the Western World in the decades ranging from the ’60s to the ’90s. Other than Yang Fudong, later Shirin Neshat, Kutlug Ataman and Anri Sala, most of this type of art was practised by artists of the “Western” world. Again, this was before the age of the internet and globalisation as we know and experience it today. Nonetheless, this book is a useful introduction on how advances in technology so rapidly changed the face of an art practice that in five decades it has become a fully immersive mechanism capable of providing constant surveillance, documentation and manipulation among other things.

COMMENTS