“I am not really an art historian, so I had no interest in Warhol’s influences when he had the idea of making those cartons – if, indeed, he had any i

“I am not really an art historian, so I had no interest in Warhol’s influences when he had the idea of making those cartons – if, indeed, he had any influences then. I am reasonably certain that Warhol had not read much philosophy. But I felt I saw certain philosophical structures in the pairing of an artwork with an object it resembled. In fact, philosophy is full of such examples, such as the contrast between dream and perception when the content is the same.” Thus speaks Arthur C Danto in his last book, What Art Is, published by Yale University Press in 2013 (the same year in which this extraordinary philosopher of art died). The small volume is a collection of six essays, mainly dealing with a basic and primary question of art and philosophy, a question that often becomes a common territory between the two disciplines, and a concern that haunted Danto for years as he addressed it in separate stages and in several of his books of reviews, essays and lectures.

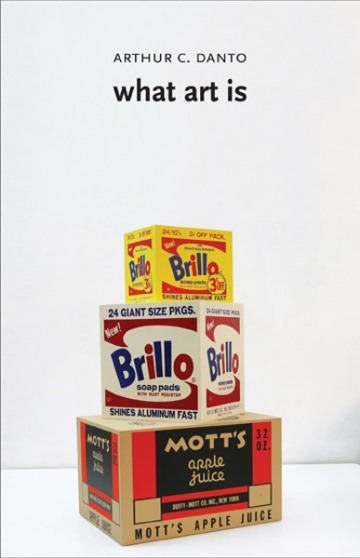

That primary question is the debate or difference between art and life, or reality and its reproduction. Ranging from Plato’s Cave to contemporary philosophers, each thinker answered or tried to answer this in his own way, and Danto (actually a man of philosophy, who came to writing on art later) was also involved with this query, often using Andy Warhol’s work Brillo Box as an example. It is difficult to distinguish or differentiate Brillo Boxes made for supermarkets and ordinary consumers from the Brillo Boxes created by Andy Warhol, because both look identical in appearance.

Danto discusses this difference, and states it to be distance in meaning and intention, in his opening essay ‘Wakeful Dreams’. He suggests that an object is art because it embodies meaning, an idea that is found in his previous books such as Embodied Meanings, Beyond the Brillo Box and The Transfiguration of the Commonplace, but now extended it by describing art being dreams in reality.

The concept of art as a parallel reality is projected in his other writings and can be experienced in this book too, but for Danto this parallel reality is constructed through the intention and idea of its maker. Providing the example of Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain, Danto argues that the French artist fully recognized the non-mimetic potential of art; even though mimeses has been considered part or even the essence of art since the period of Ancient Greek philosophers (even though they never used the word ‘art’ in those times!). Danto quotes Duchamp’s writing on Fountain (which was signed as R. Mutt, 1917): “Whether Mr. Mutt, with his own hand made the fountain or not has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an ordinary article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view – created a new thought for that object”.

Arthur C Danto shares intriguing information and interesting dimension into this debate that the initial (or original, if it can be called original!) urinal chosen by Duchamp as work of art and sent to the exhibition sponsored by the Society of Independent Artists, “appears to have vanished from the face of the Earth. Not even the Museum of Modern of Modern Art was able to find one for a major exhibition of Duchamp’s work.”

The urinal or Fountain led to Andy Warhol’s Brillo Box (in which it was the idea that distinguished reality and art), subsequently engaging Danto in expound ingon these philosophical issues, which are taken further in other essays, such as ‘Restoration and Meaning’, and ‘The End of the Contest: The Paragone Between Painting and Photography’. He elaborates on the theme of reality and replica, or original and its meaning through the restoration work conducted on Michelangelo’s fresco in the Sistine Chapel. For him the original can be the painted surface made by the hands of the great Renaissance artist, as well as the work, which changed its tone – and became darker – with the passage of time, because like the patina of bronze sculptures, the layers of smoke and dirt collected on the painted surface added to (the intended?) meaning of the work.

The book is full of such philosophical comments, questions and contradictions, and even though it is a thin publication (only 156 pages of the text), it leaves a reader enthralled – not only with the depth of art, but by the breadth of Danto’s grasp of these issues, and his mastery in expressing complex concepts in eloquent prose and engaging tone. Hence this last book (the title of which echoes his earlier book on philosophy, What Philosophy Is, 1968) affirms his status as one of the greatest thinkers and writers on art today.

Aamna Hussain is a Lahore-based independent curator and art writer

COMMENTS