Faizan Riedinger highlights the pivotal role of the transforming subject in both verbal and visual communication. The inherent nature of stories (

Faizan Riedinger highlights the pivotal role of the transforming subject in both verbal and visual communication.

The inherent nature of stories (or narratives) are structured and contain elements that, ideally, have to be communicated. With regard to an attempt to understand such an idea further, Greimasian semiotics introduces the idea of “transfers of objects” and “communication between subjects.” In simple terms this would be a discussion about how information is passed from one state to another in a story, and the role of the person telling the story (the subject).

The importance of a “transforming subject” is emphasised in understanding the dynamics of a story. This transforming subject is crucial for the syntactic organization of a narrative – how the story is structured in terms of its language and meaning. Now, there are two possibilities presented: Griemas suggests a somewhat complicated dual system: the transforming subject is identified with a ‘virtual’ subject in disjunction with the object of value. On the other hand, the transforming subject is identified with a ‘realized’ subject in conjunction with the object of value – here, value is the term used to denote cultural modes of behaviour.

In simple terms, the author is here discussing different ways the storyteller (the subject) can be related to the content of the story. Furthermore, he broadens the perspective, stating that verbal communication is just one form of communication. Communication can use various means and can be broken down into a “causing-to-know,” which is essentially a process that transfers knowledge or information.

To relate this to the production of art, we can think of an artist as the “transforming subject.” The artist’s role is crucial in how the story or message is conveyed through their art. The choice of medium, style, and the relationship between the artist and the content all play a part in the “syntagmatic organization” of the artwork. Essentially, Griemas suggests that understanding this dynamic is essential in comprehending the structure and communication of both stories and art.

Such an interpretation, although it is still limited in its field of application, can serve as a point of departure for a structural formulation of what is sometimes called perspective – in our case, when discussing art, the position(s) taken by artist and audience.

Faizan Reidiinger, in his own quiet and unassuming way, could be said to be a storyteller who functions in both visual and conceptual domains. We can also, with some levels of both assumption and imagination, trace certain aspects of methodology and expression centered on form and colour, within his oeuvre, which in parallel, also indicate the presence of participative communication, because in the process of investigation, we may find it interesting to note how certain works shown contained demonstrative components of legible storytelling.

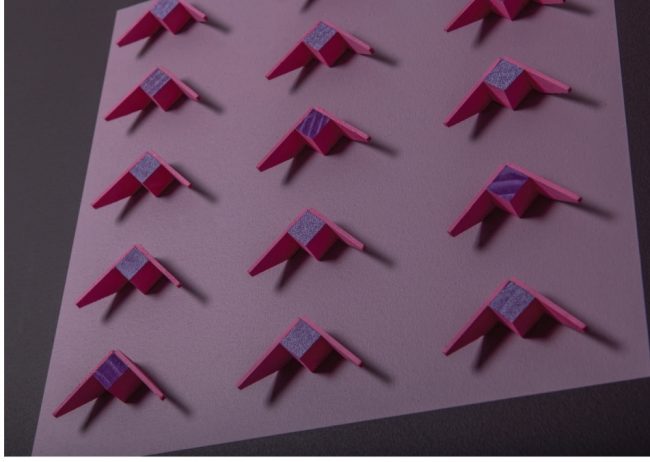

In Riedinger’s present work light, shadow and composition appear to be structured communicative elements. In our own times, we are not only familiar with these since, technologically, our very culture is constituted by moving images to such an extent that our notions of what amounts to narrative are in a state of confusion. We know that these elements are often emphasized for understanding the visual dynamics of a story, as well as considering them crucial for the syntactic organization of a narrative.

Within the production of Art, we are more able to speak of artists as the “transforming subject” , since the artist’s role in conveying the story or message through their work is an accepted idea, and this is a theory put forth by semiotic analysis of the artist-audience axis. Again, the artist considers the choice of medium and style, and therefore without fail is responsible for that very artist-content relationship in the actual organization of artwork, which is essential for the comprehension of the structure and communication of both stories and art (or of stories in Art, as it were).

To further analyse this body of work we are able to quote Humayun Memon’s curatorial note in full, since it affords a text from which we can take certain points of departure:

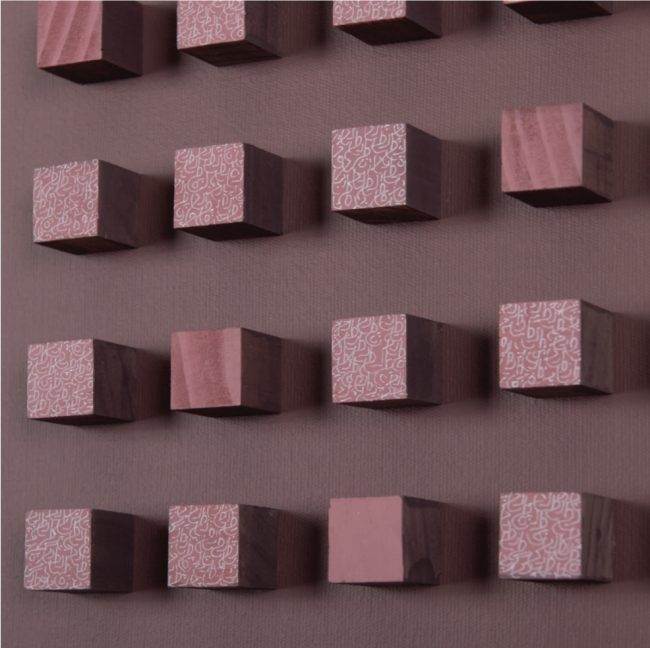

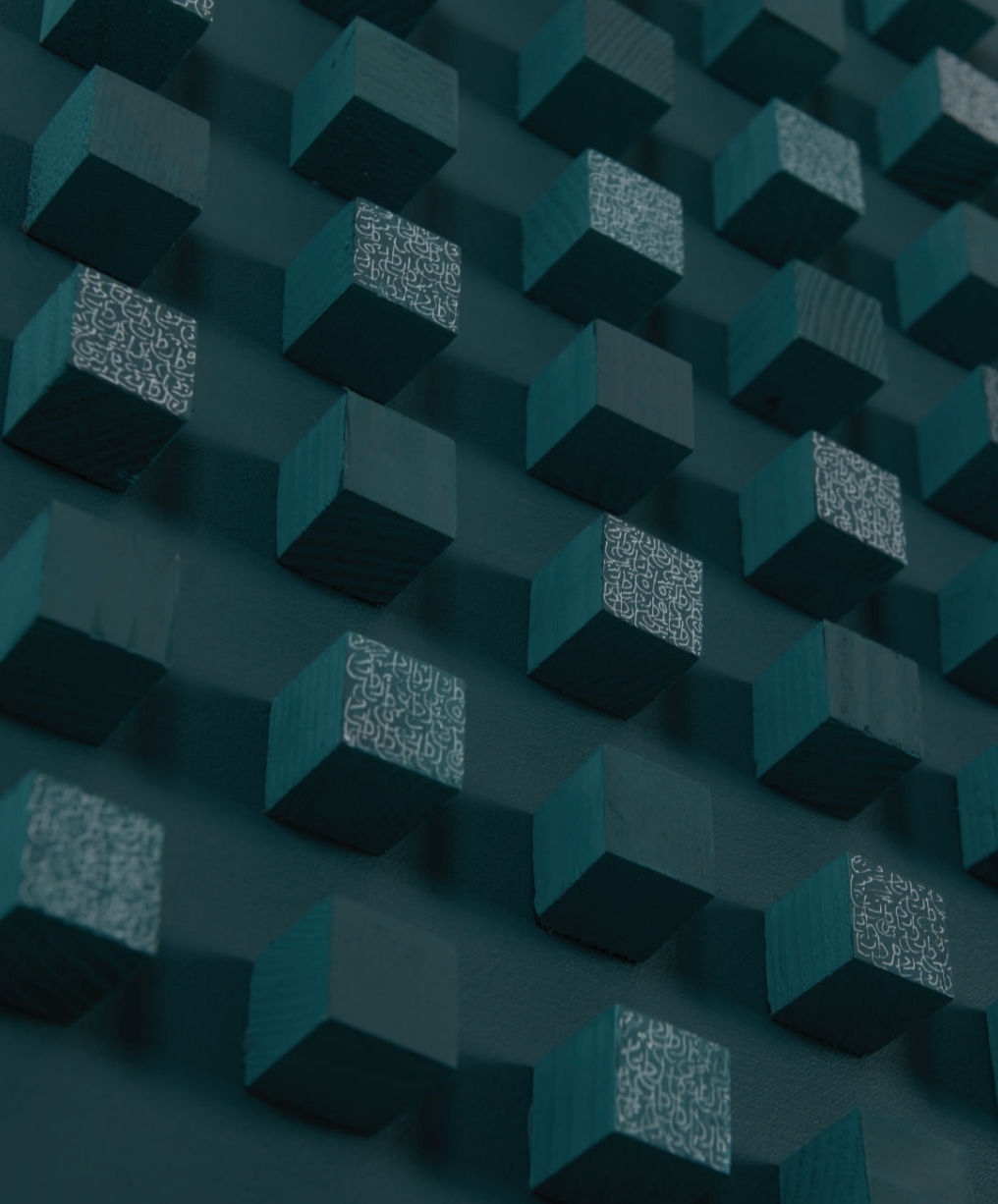

“Moving beyond his known black and white works on canvas Faizan’s third solo “Cognitive Constructs” consists of 26 artworks on canvas, three different types of wood and glass. Through the interplay of his gestural abstract calligraphy, muted colors and three dimensional forms, Riedinger prompts us to question the structures that influence our perception of self and others. Meticulously cutting, painting, gluing and working on individual pieces of pine wood, Faizan has moved out of the two dimensional canvas in “Transitioning Stage 1,2 & 3”. Similarly, in “The Monolith” and “The Five Pillars” strips of balsa wood have been used to create a canvas on a canvas. An ode to his “Expansion” series from his second solo in 2021, Faizan has also taken his experimentation on glass forward on a larger scale in the new series “Inner Light”. Staying true to his meditative style this show adds a new dimension to Faizans work as he explores thought, color and forms while serving as a testament to his journey as an artist”.

Let us pay attention first to ‘gestural abstract calligraphy, muted colors and three dimensional forms’. Riedinger’s gestural abstract calligraphy is indeed already a signature form of the artist, Further on, there are two undercurrents delicately signaling their identities – a matter of precedence, perhaps of faint but discernible echoes. The muted colours in mention are highly reminiscent of what, in the 90s, was a highly influential concept in the world of fashion. Ton sur ton is the french for tone-on-tone. It essentially refers to clothing that uses a single hue for a set of clothing, but is treated in multiple ways using texture and reflectivity. In Riedingers case it is surely an incidental situation, possibly a manifestation related to his sensibilities and ‘meditative style’ and unification of palette. Only the work title ‘Southern Blues’ differed in so much that it used a set of two complementary colours, and thus gently drifted towards the early Op Art of Russian artist Victor Vaserly.

It is in Memon’s words about the artist’s adaptation of a three-dimensional language of assemblages that we are able to Riedinger’s intelligent working-out of both the communicative aspects and stylistics, and the latter itself is the product of a narrativising relationship between the artist and the curator. Firstly, Riedinger explains the intent of the title – Cognitive Constructs – as being, quite simply, a message to his audience that ‘paintings’ or works that are primarily chromatic in style, need not be restricted to two-dimensional forms. And secondly – the integration of Riedinger’s ethos as an interdisciplinary artist (he is also deeply involved with audio production and in fact produced the ambient soundtrack playing during the exhibition), and that of Memon’s as a professional photographer operating primarily in architectural photography is located in what could be called the evenemential – the formation of (in this case) a cultural event.

To further clarify this statement we can observe that Riedinger not only places the elements of the assemblages on grids, but also paints onto the grid the linearity of shadows that would be cast were the works lit directly from an angle above, as is usually the case in galleries and homes. Riedinger also speaks of consciously having taken into account Memon’s modus operandi of creating moods with lighting.

Following all the considerations above, Cognitive Constructs, in the final analysis, represented an interesting development in the ideally bipartite relationship that is said to exist between artist and curator. Both Riedinger and Memon acknowledge the dialogical form that their exhibitions now essentially manifest.This was subtly functional in the ‘logical progression’ of this exhibition. Memon’s curatorial instincts focused on the principles that guide Reidinger’s – literally the illumination of the human spirit – and the fact that in recent years Riedinger has always included installation art using light and glass. These ‘final’ constructions if one may call them, by way of speaking of how Riedinger is constantly seeking to concretise or translate his spiritual and creative powers, were again present, but in the deepest recesses of the gallery.

Thus, we are reminded that every narrative, in order to qualify as such, must have referential points of upsurge and conclusion, and all that which occurs in between is precisely that which we recognise as an event imbued with historicity, whatever the temporal time-frame may be. The developmental aspect – the thoughtful playing out of a story that both Riedinger and Memon seemed to engage in – was evident in the way the exhibition was structured ‘in terms of its language and meaning’, using placement, light and shadow. This afforded visitors a new understanding of contemporary ways of creating exhibitions that are full of just those narrative values that allow them to be called cultural historical events in their own right.

COMMENTS