The standard book of art history used in many art institutions across Pakistan is Art Through the Ages. Normally, students treat this book like a scar

The standard book of art history used in many art institutions across Pakistan is Art Through the Ages. Normally, students treat this book like a scared text, since for them everything written about art of various periods and from different regions in this volume is as true as words of a divinity transcribed in one of the holy books. While teaching art history, a lecturer often comes across discoloured photocopies of its chapters circulating among the generations of students struggling with the history of art.

Mainly because history is a difficult subject for most of them and history of art is even more like a cumbersome burden. It would be interesting to investigate how the idea of history exists in Pakistan, a region that has a past of more than five thousand years and a state that has a history of 67 years. But whether from the angle of region or the state, the past is always contagious, since there have been attempts to link (or reduce) the history of this country either with its independence in 1947, or on the invasion of Arab warriors under Muhammad Bin Qasim, or through the archaeological findings of Indus Valley Civilization.

In all these versions, it becomes clear that history is not an authentic or monolithic entity. It keeps on changing its content and course on the basis of people who record it (contemporary) or collect and compile it (in later periods), and interpret it (even in distant centuries). An apt example of this phenomenon is the way history was modified – rather mutilated – during different governments in Pakistan, particularly under the military dictatorship of General Zia ul Haq. Each regime altered the events of past to suit its political aims and justify its acts – and atrocities. Hence if compared, the text books of history in Pakistan printed in the period of democratically elected prime minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto described the importance of electoral process/course in the struggle for Pakistan’s creation, but in Zia ul Haq’s era the movement of Pakistan was described as a means to implement Islamic laws and ideology in a country without secular or non-Muslim contingents. In the same lieu, historical figures such as Dr. Muhammad Iqbal and Muhammad Ali Jinnah were altered according to the political requirements of the times. So in an atmosphere of liberal thinking and Western modernization, both leaders were presented as unorthodox Muslims, well versed and interested in Western ways of living, dressing and thinking (with Jinnah portrayed in immaculate suits and ties). But in a more religiously charged period, these two were turned into pious personalities, conveniently ignoring that one drank and other ate what were not allowed by the faith. Instead their love, devotion and dedication to Islam was projected, so much so that the image of the two fathers of nation started to feel like of men with flowing beards and wearing non-European attire (contradictory to factual record/photographs).

What happened in Pakistan takes place in other societies too; hence in the words of Delhi-based Urdu literary critic Shamim Hanfi, all books of history are works of fiction, whereas fiction of a time provides its true history. In a similar manner the history of art suffices more than what it is expected from it. Perhaps the first attempt in recording the history of art was Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Artists in two volumes (first published in 1550), in which he provides accounts of painters from Renaissance Italy. The book in a way blends storytelling with factual recording. Yet a reader from a later period can pick more than what was intended by the Italian author. His personal preferences, subjective judgement in art, prejudices and biases can not be detached from his ‘history’. It was only in later periods that a more realistic, natural and neutral approach towards history was sought, but even in these volumes and texts, one could trace the personal and cultural positions in art history; which subsequently transform and present new versions and views of the same works, makers and movements.

The example of Art Through the Ages is a prime case in this regard. Now with its 14th edition in circulation, the book was first published in 1926. If one compares its different editions, one realizes how the approach towards what is art and what can be history has changed through the ages. In earlier editions, the focus is more on the Western European art, with its origin in Greek, Egyptian, Mesopotamian civilizations and in prehistoric caves and carvings. But later volumes include art and culture from other cultures, such as Islamic, Indian, Chines and Japanese. However only in the latest editions one finds chapters on African, Asia Pacific Islands, Pre-Columbian and Aboriginal Art. Yet the division of discussion is intriguing, because in all editions, no matter if it is 3rd or 13th, the Western art is described more like a coherent narrative, with the idea of progress clearly communicating through this structure. As different chapters advance from one movement in art to next, and inform how influences have spread – but only in the same geography, of Europe. Ironically when it comes to other nations and societies, the sense of time or the aspect of development is not necessarily conveyed. For instance, the chapter on African art deals with Africa as one uniform group of people, in which vast areas and separate eras hardly affect the pictorial practices of people living in places as distant Nigeria is from Zambia, or as disjointed in times, like from 16th century to 19th century. Also the division of time in Christian calendar to map the African Art conveys the supremacy of European scheme of denoting, describing and defining the world.

As Arthur Danto says, human past is divided into history and cosmology. “I have, I must confess, not seen it anywhere said that the great climactic event, which divided the period of cosmology from the period of history, was the creation of the human female.”[i] In a similar sense, the art of nations constituted outside the Western canon are regarded as ‘ahistorical’. But more than that the exclusion of non-European culture from the mainstream art narrative is justified on the pretext of quality and high standards.

This division of disciplines and territories on the basis of ‘quality’ or on the premise of a ‘standard’ of art is not surprising, because it was only in the second half of the 20th Century that works out of Africa, Oceania and Pre-Columbian cultures were considered art, and not as artefacts or pieces of craft. That period witnessed a bridge between classification of High Art and Low Art. And not only in terms of including chapters on other regions; a number of pictorial practices, which were never regarded as art, such as the quilt making and pottery etc., were accepted as being art. In that sense the comparison of art history or books on art history is a chronology of changing notions of art and evolving definition of history.

At some point one feels the need to be politically correct and culturally conscious and one may criticize the routine or tradition of not including art from the periphery into a major text on art history, or even if it is incorporated, then being marginalized, not discussed in the same tone or treatment as the European art history. However, in art and other matters of intellectual debates, one can not afford to have an all-inclusive approach, and apply an equal-opportunity policy. At a point one needs to act upon some notions/parameters of quality (no matter how arbitrary those are!), which reminds of Saul Bellow’s response on the issue of world literature when he announced that he will read African writers if they produce a Tolstoy.

The selective process, which segregates the works in terms of their aesthetic standing in the tome of art history is an issue debated over. Because the standards of art are set on the basis of European pictorial practice and taste, anything outside that sphere hardly makes a place in the supreme sanctity of art. At the same instance all the discourse generated on art is in languages/sensibilities derived from the West, therefore it is impossible to include other regions in it. Therefore, because of this exclusion works from other regions are always perceived as alien or outsiders, a state that keeps on aggravating due to its mechanism of separation and ‘sophistication’.

In that situation the question arises for many on how to deal with the mainstream art history and a parallel history of art. But along with history there are other areas of knowledge/education in which unconsciously or traditionally the supremacy of one culture is established on others. For instance, cartography, otherwise a scientific subject, also communicates a political or colonial content in the way the global map is drawn for the whole world. In our standard atlases, the world’s direction is depicted in such a scheme that Europe is on top of Africa, or USA is above from South America. A number of artists and publications challenged this otherwise normal and natural practice, which establishes and enforces the colonial and Western agenda by twisting the world map from North to South, such as on the covers of Beyond the Fantastic: Contemporary Art Criticism from Latin America [ii] and and Himal Southasian magazine, which presented a new world order, with South or Asia being on top.

Art History also demands such steps that redefine the boundaries of aesthetics, which in essence are the feature of European taste in art. In order to deviate from these and set new parameters, one needs to recreate and revise the canon of art history, which projects the standards of art history as aesthetic yardsticks, but in actuality are the marks of political superiority in the name of cultural constructs. Hence the concepts of good taste and high art, when come to be classified in the folds of art history, are stained with the Imperialist ideas.

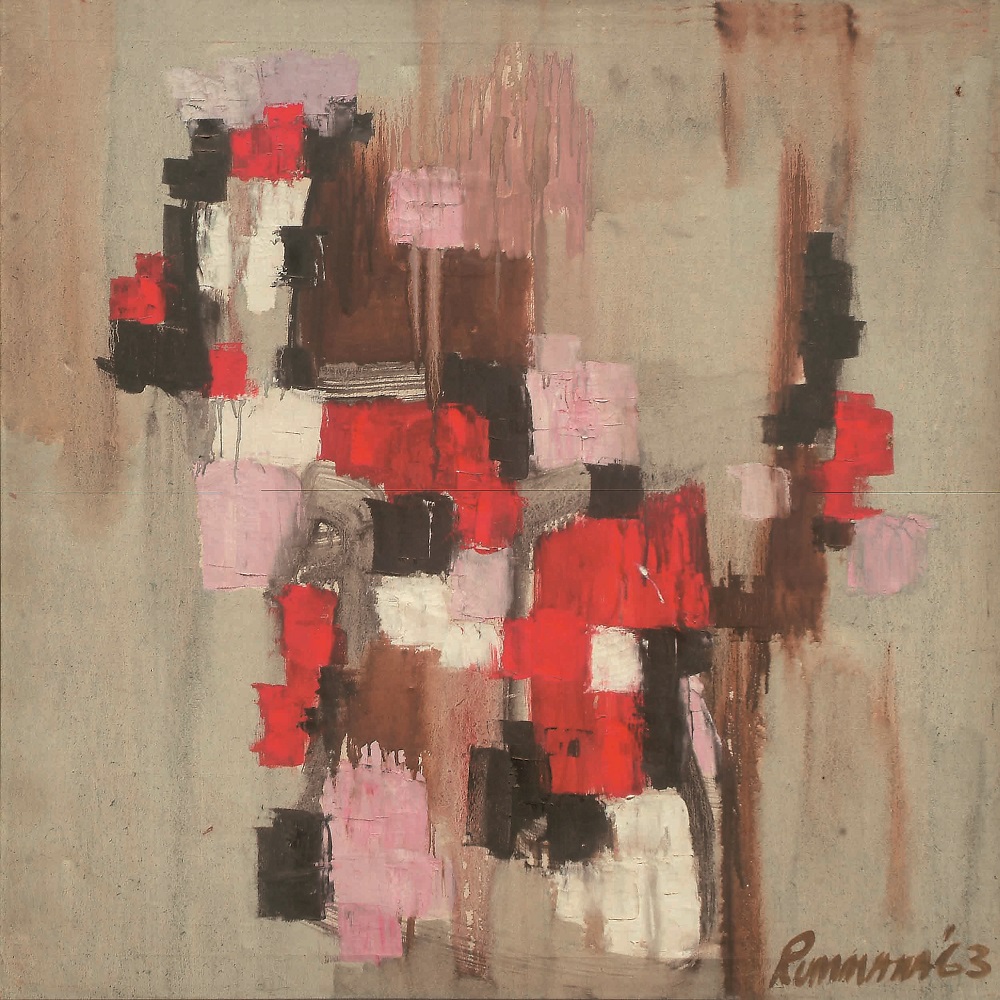

The impact of political agenda can not be divorced or neglected from the making of art history. One of its examples may be observed in the way history of Pakistani art has been written. Although the country still lacks sufficient number of trained and practising art historians, yet there have been a number of books on Pakistani art. Interestingly, in some of these the issue of Bengali artists, who were part of Pakistani art’s narrative is dealt in a peculiar manner. In the first book, Art in Pakistan by Jalal Uddin Ahmed (published in 1954) one could not find a divide between artists from Eastern and Western wings of Pakistan. The classification is more on the basis of genre and generations. In the second book on Pakistani art, Painting in Pakistan by Ijaz ul Hassan (printed in 1991), one can see the similar sort of classification. So instead of separating artists on the base of their regional identities, they are discussed according to their visual concerns and pictorial practices. Hence, painters like Aminul Islam, Murtaza Bashir and Syed Jehangir (from East Pakistan) are mentioned along with Raheel Akber Javed, Ajmal Hussain and Lubna Agha (from West Pakistan) are in the same chapter; or one reads about the works of Mohammad Kibria (from Bengal) side by side with the works of Iqbal Geoffrey, Zahoor ul Akhlaq and Gulgee (all belonging to Lahore and Karachi).

In the other two books on art from Pakistan, Contemporary Painting in Pakistan, by Marcella Nesom Sirhandi, (1992) and Painters of Pakistan by S. Amjad Ali (1995), artists from former East Pakistan are discussed, but now in segregated sections highlighting their links with former province. In another important publication on Pakistani art, Image and Identity (Akbar Naqvi, 1998) one does come across separate entries on individual artists from East Pakistan, but in a small sub-chapter under the heading of “The Bangla Association (1947-71)” with space allocated to all those artists not bigger than granted to single artists such as Gulgee, etc. However this was perhaps the last major book, which mentioned the artists from a lost past, because in all the latter books, one cannot locate any traces of that part of (art) history that was sliced off with the liberation of Bangladesh.

An attitude to history and history of art that is not surprising because history writing is a process of eliminating and enhancing. It serves the purpose and demands of the politics of its times, which require to conceal certain incidents, personalities and concepts from the public’s views and memories. Milan Kundera talks about this aspect in his novel The Book of Laughter and Forgetting [iii] quoting the case of a leader of Czechoslovakia, who after the Communist Revolution was photographed on the presidential balcony along with his comrades. Due to the freezing cold, his colleague borrowed his woollen cap, and after some years when the leader who lent his hat, fell from grace and was wiped out (air brushed) from all the pictures, only his woollen hat remained visible.

Somehow in the narrative of Pakistani art history, a strong section of East Pakistani painters have been slowly erased, and no one knows but speculates that what other components in our larger scenario of art are not presented/represented. Something that turns the history of art as the story of art, each time told with a different point and position.

Quddus Mirza is Editor of ArtNow Pakistan.

[i] Danto, Arthur C. What Art Is. Yale University Press: New Haven & London, 2013 (page 70)

[ii] Mosquera, Gerardo. Beyond the Fantastic: Contemporary Art Criticism from Latin America. Institute of International Visual Arts: London, 1995

[iii] Kundera, Milan. The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, Faber and Faber Limited: London, 1980 (page 4)

COMMENTS