A difficult and daunting task for a creative individual is to be detached from his/her creative practice, and see the works of contemporarie

A difficult and daunting task for a creative individual is to be detached from his/her creative practice, and see the works of contemporaries through the lens of their makers. A challenge, but in reality a manageable endeavour – normally called curation, if executed by individuals trained in multifarious fields of art and design.

Four curators, the recent graduates of National College of Arts and Beaconhouse National University, and participants of Curators’ Residency (a collaboration between Vasl Artists’ Association Karachi, Gasworks London, and The British Council Pakistan) actually proved that nothing is unattainable in the realm of art, while adding a layer of fresh context to works created by artists of various disciplines, experiences, and concerns. That context can consist of a shift in venue, a change of display spaces, a varied audience, but more importantly the unique vision and version of the curator compels a viewer to look at the works through an altered eye, hence known pieces and practices appear different and distinct.

This phenomenon was spotted at the opening of Curators Residency’s four exhibitions, simultaneously held in Karachi; on locations, which varied in terms of scale, function, neighbourhoods and social conditions. Ranging from a Vocational Training Centre in the heart of Lyari, to Full Circle Gallery in Clifton, and the Theosophical Society Library. Even the regular space like a functional gallery, or a peripheral place like a community centre, or a locality completely outside of an art circle, such as a dysfunctional and ignored training institute for the poor of the poor, the four curators managed to transform the original usage, identity and appearance through their interventions.

Sehrish Mustafa, Rameesha Azeem, Ghazala Raees, and Asavir Nadeem were selected through an open call for a yearlong project, which included group discussions, lectures, visits to the artists’ studios and collectors’ residences, along with galleries and museum’s tours, public seminars, and an intense period of 10 days travel to UK’s art institutions, display centres, important exhibitions, and meetings with curators, artists and experts in varying areas of art. All culminated into 4 shows on 28th April 2024.

These shows, spread to different sites, offered a glimpse into the future of Pakistani art, both in terms of emerging artists, and a new generation of curators. Each curator coordinated with artists to formulate a new definition of curation. A term/profession often misunderstood and mostly misused, is significant today, because a curator functions like the director of a movie. A film director works with actors, script writers, music composers, playback singers, cameramen, stage designers, costume makers, etc., to produce original and unique artwork. In such a way that a recognized and adored star turns into a totally opposite personality, through an intelligent and successful strategy of the director.

Similarly, the four curators attempted to present familiar themes, known artists, and normal practices in such a light that visiting every exhibition was a shock of the new.

Asavir Nadeem tried to question the traditional role and institution of an art gallery, by modifying it into a stage for street performers. Thus on the day of the inauguration, one came across a magician, a sand artist, a snake charmer, a golden man, an impersonator, and a spider man busy parading their talents and tricks in front of an audience accustomed to see art on the walls, on pedestals, or projected by visual artists. At her curatorial project ‘Practice-in-(g) Performance’ visitors were encountering a segregated (normally under-privileged) category of creators. However, for a few the entire idea of bringing entertainers from public arena to a posh setting for viewers to be amused by these individuals was problematic. Because even if Nadeem sought to highlight the divide between art and life, still the modus operandi in some way converted these people into exotic spectacles. Not dissimilar from going to a zoo for gazing at strange animals, birds and reptiles (keeping a safe distance, marked by the metal rods/cage), belonging to regions far and disconnected from one’s routine existence. At the Full Circle gallery, the distance was not tangible, but socio-economic.

The concept of concentrating on gaps, and bridging them was the core theme of Ghazala Raees’s exhibition ‘Creation in Translation [case study 01]’, which involved eight artists of multiple practices. It documented two-way dialogues between creative personalities, manifested in different formats, on view at the Theosophical Society Library, Jamshed Memorial School. Raees briefed her artists to come up with a text, and then exchange it with one another, thus each work had two creators: the provider of theme/content, and the executioner of the actual piece. An interesting idea, which led to some unusual artworks. Like Sohail Zuberi’s monochromatic manual photo transfers on glass, displayed inside the drawers of a wooden cabinet, a decision that suited the atmosphere of an old library. Another remarkable work was created by Haider Ali Naqvi, based upon the text written by Ayaz Jokhio, later transcribed in sign language, and engraved on a panel of dyed granite by Naqvi. Looking like information material one usually finds in historic and public buildings.

If the other participants of this project adopted an expected path: translating words into images, Naqvi, brilliantly, converted the script into another script, made of pictorial characters. Making a viewer realize that words we read and write are also visuals, and if you don’t know the script of another language it becomes merely a pictorial matter. Like Chinese, Japanese or Hebrew alphabets, which are shapes devoid of meaning for a non-speaking person. The language, its presence, absence, function and limitation were explored in Sehrish Mustafa’s curated show ‘Afterwords’. Comprising five artists, the exhibition impressed the viewers due to its curatorial clarity, scale and diversity. It was also a commendable example of how a curator transforms the site, physically and conceptually. Situated at Lyari, the most unusual background for an art event, it surprised a spectator the way Haji Abdullah Haroon Vocational Training Centre – a delipidated, disintegrating and disused structure, was metamorphosed into a suitable space for video projections, site specific installations, mixed media sculptures, paintings and works on paper.

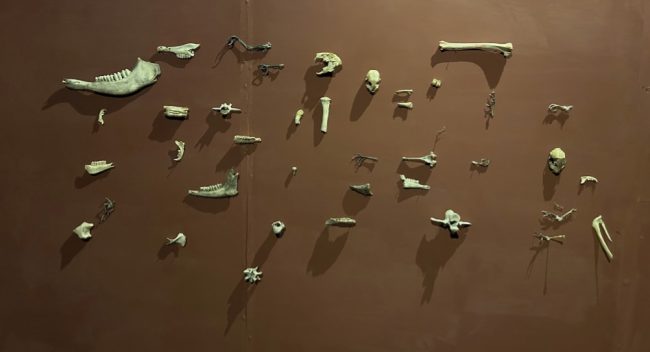

Generally the art activities are exclusive and removed from the public living in under-privileged neighbourhoods, such as Lyari, but ‘Afterwords’ invited and engaged people from the surroundings, as was observed on the day of opening. Visitors were able to identify with works on display, like the interactive video projections of Wajeeha Batool, and the use of materials such as the fur, bones (Mariyam Zia), concrete blocks, metal rods, clay pots and burnt furniture (Danish Gahlot) which were relatable to the street, small shops and the location. Wajeeha Batool’s video on the floor (A Fish Tale) mapping water and fish, particularly attracted and encouraged the audience to step on the virtual picture and discover how the ripples followed their footsteps. Hence the barriers between high art and the general public were suspended.

The show, as indicated by its title, was focused on what takes place beyond words. Mustafa in her curatorial note discloses that to these artists “histories and stories have influenced their sensory, collective, and corporeal formation”. She observes that the “experience through our senses is what makes us human, not only as one self but also in our relationship with separate and split identities”. Illustrated in the choice of participants and allocating spaces for every work. On entering the corridor of the display area, a viewer was exposed to Aisha Suria’s personal, intimate, sensitive (and disturbing) imagery, made accessible through a deliberate decision to employ the visual vocabulary of a kid or a lay person. Adjoining room contained Maryam Zia’s mixed media sculptures which evoked the sensation of death, decay and destruction managed through substances she combined and appropriated. Repeated in the installation of Danish Gahlot (In the Wake of a Nightmare) encompassing a dark space, crowded with scorched items, scattered like the aftermath of a disaster.

The theme of death and demise continued in Gahlot’s other work too, constructed in the next room. Round clay pots were arranged in a large circle, each covered with red cloth and topped by small terracotta plates filled with ashes of various organic origins, like wood, dried vegetation; and one pot that had a flowering plant. The symmetrical composition of identical pottery was regularly highlighted – almost pierced by the shaft of a slowly rotating green laser, illuminating each object for a few seconds. The work, called Eternal Return, was associated with the idea of reincarnation of life in multiple forms.

Reincarnation, or recycling of life and death was again conveyed in Danish Ghalot’s Ruins of the Day, a site specific installation in the main courtyard of the Vocational Training Centre. Intriguingly the pile of debris in the middle square seemed the part of nearby disintegrating domestic structures, hence reminding the need to reflect on how nature has been affected through urbanization in a metropolis like Karachi.

The ecological problems are as crucial in Lahore as in the industrial city of Karachi. So the environmental upheavals became the major concern of Rameesha Azeem’s exhibition ‘Harmony in Design: Sustainable Architecture & Art’, at the Theosophical Society Library, Jamshed memorial School. Azeem invited three professionals from separate disciplines (art, fashion design and visual communication design) to reflect on the theme through their individual positions. Kashmala Khan by employing AI concocted views of a town resembling Lahore, engulfed in layers of smog. Humans, animals and buildings were enveloped in a coat of grey tone/substance, besides some being under a length of transparent fabric. The environment was a delicate/desirable point of departure for Mahrang Anwar. Trained as a fashion designer, Anwar produced a two-channel video (Subliminal Sustainability), preserving the common practice of recycling ordinary stuff around us. Like reusing old towels as floor mops; henna paste for a fabric dye; tin boxes of imported biscuits recycled for storing sewing supplies; a “common transparent plastic bag” turned into a handbag to put “important documents, mobile phones, Identity cards and chargers”; etc.

Similar concerns were evident in Anwar’s three-dimensional construction, Polymorphism of Textile Waste, fabricated with waste fabric scraps, marble dust, resin, and designed like an open shower, composed of disused pieces of fabric, reinforced into tiles, which apart from their aesthetic value and variations suggested ways to reutilize familiar stuff in an exciting, relevant and unique manner.

Akin to the exercise of curating, which – like the recently concluded Curators Residency – is a means to comprehend extraordinary content, context and connotation of an ordinary existence, and works emanating from it.

COMMENTS