Kiran Saleem's solo show "History within History" was held at the Canvas Gallery, Karachi. “Shakespeare, Rembrandt, Beethoven will make films...

Kiran Saleem’s solo show “History within History” was held at the Canvas Gallery, Karachi.

“Shakespeare, Rembrandt, Beethoven will make films… all legends, all mythologies and all myths, all founders of religion, and the very religions… await their exposed resurrection, and the heroes crowd each other at the gate.”

– Walter Benjamin, ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’, 1936

By definition, painting as an expression of postmodernity has segued away from its origins as expressive of the archetypal imagination, veering towards the anachronistic and glacial hyperrealism of bulletproof advertisements adorning print and digital media. Surrounded by this calculated assault of the collective sensorium, it is refreshing to view a proverbial Return to Innocence of the palette and brush, inherent in Kiran Saleem’s solo exhibition ‘History within History’, on display at Canvas Gallery, Karachi from November 28th – December 7th, 2023. In an arch twist of fate, Saleem’s simulated reproductions of European Old Masters, paired with deeply personal photographic mementos, represent a departure from Baudrillardian philosophies of repetition. The philosophical tangent on display is not one of the direct-positive process of a mere daguerreotype; rather an inherent link to deeply personal and filial stories. Each painting on display in ‘History within History’ is paired with an Ultraviolet print of a photograph capturing the artist’s family members in similar contexts to the original replica of the European school of realism, in a manner whereby the gaze is confounded in its schema of reality… Do the pieces of innocuous masking tape seemingly tacked on to large swathes of negative space on Saleem’s canvases indicate a wry barb aimed at deconstructing the Conceptual School, or are they pointedly caricaturing the polymorphic symbiosis between print media and the Fine Arts? With Kiran Saleem’s vaulting ambition, they are both, and indubitably more.

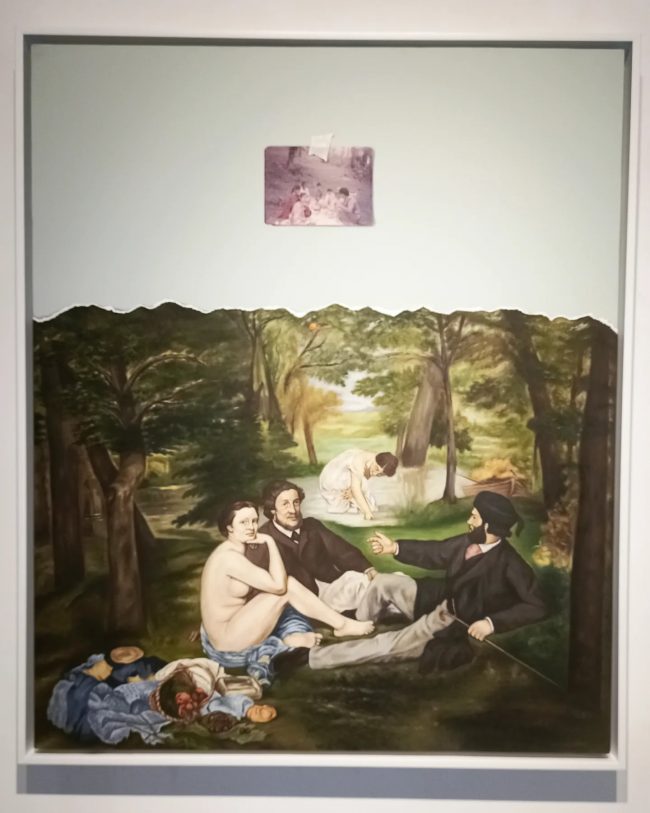

Approaching her mid-career era of established practice, with two Master’s degrees under her belt, Saleem has built an oeuvre to rival most Low Countries artisan guildsmen or apprentices toiling in Italian Renaissance Master’s workshops. Were it not for the prescient documentative quality immanent in each narrative created by family history, one would not be mistaken in gauging verisimilitude to be this body of work’s modus operandi. However, upon closer examination, each piece unfolds an interwoven universe on its own spindle of art historic compulsion: a prime example being the viewer drawn magnetically to the grandiose splendour that is Manet’s ‘Le Déjeuner sur L’Herbe’ in Saleem’s ‘History within History III’ (Oil, Acrylics, and UV Print on Canvas, 36 x 30 Inches), while quizzically gazing at the counterpointed photo above it, depicting a group of picnicking individuals. Painted in 1863, Manet’s controversial depiction of a nude woman seated amongst fully clothed men in a public recreation ground, created a scandal in the Paris Salon. Not only was this morally confounding to critics and the layperson, but compositionally disconcerting and seemed to thumb its nose at laws of ocular perspective: note the skewed sense of proportion created by the rather large size of the female figure in the distance, and the raised hand of the gentleman on the right – a direct reference from one of the works of 16th Century Italian engraver Marcantonio Raimondi. This enfant terrible heralded one of the hallmarks of modernism in its diversion from the Canon and thematic collage of ideological frameworks and historical paraphrasing. Thus, by incorporating this seminal piece, Saleem has mined an archive of aesthetic sensibility that honours each predecessor in turn. The family above evokes a sense of lighthearted warmth and community in contrast to the provocative imagery of Manet, yet the foundational philosophy propounded by the ‘posed’ figures marks a style of viewership entrenched in the ‘gaze’.

The gaze may be extrapolated on by the subject-object relationship, wherein the agency of the viewed is stolen by the viewer in a dance of hierarchical structures dating back aeons yet glaringly highlighted by digital media. In critic John Berger’s words from his television series and accompanying essays that captured the spirit of cultural revolution in the early 1970s:

“The contradiction can be stated simply. On the one hand the individualism of the artist, the thinker, the patron, the owner: on the other hand, the person who is the object of their activities – the woman – treated as a thing or as an abstraction”. Berger illustrates the dichotomy between spectator and spectacle, through reference to the power dynamics of nakedness versus nudity within the Western Canon and how the action-potential lay in the masculine, while the feminine historically was in many cases, designed to be ‘devoured’ by the male gaze. It is this principle that Saleem alludes to in many of her female protagonists: most blatantly so in ‘‘History within History VII’ (Oil, Acrylics, UV Print on Canvas, 24 x 30 Inches), ‘History within History V’ (Oil, Acrylics, UV Print on Canvas, 20 x 30 Inches), and ‘History within History VI’ (Oil, Acrylics, UV Print on Canvas, 24 x 30 Inches). In the former, the formidable gaze of Dona Teresa, painted by Francisco Goya in 1805, is directed challengingly at the viewer, and the austere darkness coupled with cool tonalities, espouses dramatic flair with gravitas. Coupled with the artist’s late cousin’s pose to match, the message undoubtedly transcends the medium here, to redress the gender-imbalance within the framework of the objectified. Similarly, ‘History within History V’ pairs the beatific Madonna and Child of Anton Raphael Mengs (1770-1173), with the sheer joy of Saleem’s own infancy, in the warm embrace of her arms of her mother. The archetype of Matrix or Creatrix lends demystification to the hyper-sensualised schema of ‘Modern’ Woman, while stretching the possibilities of sense-perception beyond the primal urge, to a sophistication that is post-feminist in its ambition, yet perhaps not engaged in the tangible urgency of social revolution, in this instance. More direct in its juxtaposition of the polarities is ‘History within History VI’, where the hands of a married couple commingle. In this work, what is notable is the contrast of gazes on display between the artist’s parents: a quintessentially South Asian bride with her downcast eyes, while the groom confidently beholds the beholder. Granted, this image itself is fixated in the past of another sociocultural era, yet its ghost haunts marital dynamics to this day in many parts of the world, let alone ours, and therein lies the crux of the matter: that the ideological genesis of duality is time-bound to the flesh of our progenitors, our myriad selves, and our successors through the lens of legacy.

‘History within History’ marries the mélange of legacy, with a promise of projected aesthetic vistas from which one can extrapolate the possibility of a future self-referential monologue ad infinitum. This may be irksome for contemporary proponents of the glittering shoe-gaze variety, who would prefer the latest candy-wrapped trend in the arts to be the cultural happening of the moment, yet one only has to glance at their social media feeds for confirmation of how insubstantial and ‘influenced’ this consumption is. The original influencers – the Old Masters – would turn in their grave at this cultural denuding. Thankfully, the piercing sharp minds and equally deftly skilled hands of yesteryear have serendipitously seeded themselves in artists such as Kiran Saleem and ‘History within History’ is her love-letter to tomorrow.

COMMENTS