This essay focuses on a few prominent historical figures and movements in the art history of South Asia that laid the foundation of the art we see tod

This essay focuses on a few prominent historical figures and movements in the art history of South Asia that laid the foundation of the art we see today. Influences have been large and date back to over seventy years: Mughal rule, the process of colonization and decolonization, development of art institutions and European influences. The effects of militarization, Islamization, political unrest has created interesting trajectories in the art practices we witness today. The idea of space as a physical cosmos for the artist has been re-identified to the space in the viewer’s mind.

The moment for celebration was just right. A young man in his early thirties on 15th August 1947 astutely stood in the streets of Prague in front of Czech Republic Parliament, proudly waving a self-made green flag with a crescent and a star. There to attend the first International Congress of Democratic Youth, the young artist had just heard of the historic moment of Pakistan becoming an independent state. This critical point was not to celebrate the division of the sub-continent, rather freedom from the British dominance. This energetic man was no other than Shakir Ali (1916 – 1975).

The onset of British rule over the subcontinent in 1858 brought in tremendous changes in India’s society, with a complex milieu giving rise to modernity in South Asia. They installed various art schools all over the sub-continent in Kolkata, Madras, Mumbai and Lahore from 1839 to 1875 where new mediums and genres were introduced. Academic learning was stressed on. Courtly patronage gradually diminished and artists seemed to struggle being forced to compromise their work using inferior materials. They were accustomed to using natural pigments extracted through processes learnt and passed on for generations. Trained in traditional miniature techniques and styles, they were now being acquainted to new genres of academic nudes and naturalistic landscapes.

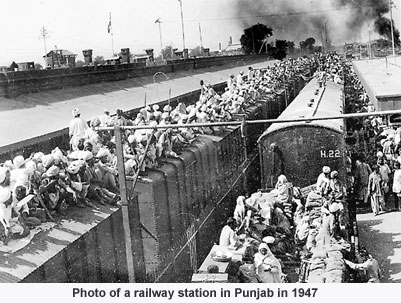

Bengal School became an influential art movement during this time flourishing throughout India during the British Raj. Led by Abanindranath Tagore (1871 – 1951) and greatly supported by the British, it emphasized on the indigenous (swadeshi) ideology of art and Buddhist and Hindu aesthetics became the core of artistic practices. A critical point in this movement was when Ernest Binfield Havell attempted to encourage students to imitate Mughal miniature. He felt that the Bengal School was not ‘Indianised’ enough and should focus solely on revitalizing ‘decorative’ art portions: he left the ‘fine’ art areas almost untouched. Therefore creating an implied dichotomy that categorized the ‘fine arts’ as a purely European study and the ‘decorative arts’ its Indian counterpart and the only area of concern for reform. With end of the 331year long rule of the Mughal dynasty, a stirring political state by foreigners, internal bubbling of emotions made the artists revolt to the idea of being ‘Orientals’. “Despite all the pain and displacement involved the experience of colonialism, the struggle for independence and the subsequent liberation stimulated artists in the sub-continent to engage seriously with modernism”. New styles were developing and names like Abdur Rahman Chughtai (1894 – 1975), who was anticipated as a Muslim artist, contributed significantly to the growth of modernity in art in Pakistan “as opposed to the nascent Hindu and national art promoted by the Bengal School” . Ustad Allah Bux (1895 – 1978) picked subjects from the Hindu and Persian mythology and moved onto his migration series depicting scenes at the time of partition. The most popular amongst these were the Heer Rajha series in the 60’s. Processes of moving from colonial to postcolonial modernity had already begun in the sub-continent.

On 14th August 1947 the time of independence was also the time when Bombay Progressive Artist’s Group was founded by six members that included M.F Hussain, S.H Raza and F.N Souza. They believed in nurturing the Indian form of modernism that celebrated Indian traditional paintings while also working towards the emergence of the pioneering development in the art forms of Europe and America. They took the Independence Day as a beginning to encourage the Indian avant-garde and to ‘paint with absolute freedom’. Ostracized by the Indian art establishment, they staged their own exhibitions. Lasting barely a decade, with members moving to more nurturing grounds in the West, this movement laid the foundation for India’s art practices for the future.

Coming back to Shakir Ali raising the new-born nation’s flag in Prague, he decided to come back to his homeland in 1951. He joined the Mayo School of Art in 1952 and in 1961 became the first Pakistani principal of the now National College of Arts, NCA. He was considered to be a pioneering modernist in Pakistan and a great mentor to post-modernist Zahoor ul Akhlaq (1941 – 1999). Ali studied at Andre Lhote’s art school in Paris and was greatly inspired by the multi-faceted painter, sculptor and writer’s teachings. Bombay artists Akbar Padamsee and Jehangir Sabavala also attended the same school around the same time. The artists were coming back to their new redefined nations, overcoming the concept of borders, language and identity. Each created modern art under a similar historical context and their respective response to tradition.

Some artists were at work before partition and contributed significantly to the art practices of later generations. They became study points for art historians and their contribution cannot be ignored. Four most prominent artists were Amrita Sher-Gil, Zubeida Agha, Zainul Abidin and Ali Imam. The same artists played a pivotal role in the formation and promotion of the arts and culture of decolonized South Asia. Amrita Sher-Gil (1913-1941) died before partition at a young age. She belonged to the artistic-intellectual elite class with a mixed cultural background. Her influence was eminent on the artists who admired her. She “addressed [her] hybrid identit[y]ies with a seemingly utopian connection of European modernism and non-European tradition, Forerunner for feminism and free sexuality; and most of all …strong female protagonists in a male dominated art industry” . It is understood that Shakir Ali decided to become a painter after he saw an exhibition of Sher-Gil in Delhi in 1937. Zubeida Agha (1922 – 1997) a strong, independent painter, carving her own trajectory on abstract, ornamental and painterly language was greatly inspired by Jamini Roy’s folk references and rural depiction. She was a strong-headed woman, much ahead of her time. She deeply engaged in the institutional development in 1961 by setting up the Rawalpindi Art Gallery to help promote young modernists. Zainul Abideen (1994 – 2002) became the tabula rasa for East Pakistan and then later for Bangladesh. He depicted rural life in Bengal before and after the advent of colonialism.

The complete oeuvre of his work provided important insights: “relationship between his ‘realist’ and his modernist works, his valorization of the rural and the folk, and the question of the nation…Abidin’s leadership in creating institutions and spearheading the development of a professional sphere of modern art in the underdeveloped region of East Bengal/East Pakistan was an important part of his work” . His practice went back to the peasant society peeking into the future dismissing the present British rule. Ali Imam (Syed Haider Raza’s brother) known for his ‘idiotic emotionalism’ as stated by Shakir Ali, taught in Karachi for several years before founding the Indus Gallery. This gallery remained functional for several years and housed some of the most important exhibitions. Many other artist names of this time can be quoted as each artist began exploring their own territories, reflecting some horror stories of the past, working on traditions and also finding creative ways to stretch themselves out of it.

Artists developed a ‘new sense of space’ and began exploring spatiality on a flat surface. They travelled, discovered, felt and became attached to their new territories saturated with instability, war, Islamization and militarization and now terrorism. All of these became unavoidable subject matters and the focus of various art practices. Some engaged with these by imitating art, others as a spectacle or in an ironic manner. On the other hand, Zahoor ul Akhlaq “addressed social issues by abstracting motifs and events into a rarefied pictorial schema” searching for a unified pattern and he ultimately became an arbitrator of post-colonial art leading to a new age of art practice in Pakistan. He explored the past to set new challenges and became the new standard for the present. Equally, a few artistic minds in this movement developed in their new found spaces: the absence of space that they were yearning for or exiled from. The exploration of this cosmos after seventy years continues, however, this time from a viewer’s point of view. The mind travels to a place that is intangible and is “reached out without reference to projecting the body into that space” . The works of art now stir excitement and exude dynamism and playfulness.

Geographical boundaries and spaces that were determined on the basis of religion seventy years ago seem to be diminishing with the advent of media and technology in contemporary South Asia. The 21st century artists today are exploring new spaces on their canvases and within the viewer’s mind. South Asia’s art now reflects its past just as it festers to the surface of the canvas. Despite this, there are claims still that contemporary art is still no different to that in any other part of the world. Artists are still on a search for ‘identity.’ It is evident that the subjective search to find one’s own artistic rhythm will continue to reshape itself in good time.

COMMENTS