There is a price to pay for apathy. One thinks of poor Gregor in Kafka’s ‘Metamorphosis’, who wakes up as a giant cockroach, unable to act and eventua

There is a price to pay for apathy. One thinks of poor Gregor in Kafka’s ‘Metamorphosis’, who wakes up as a giant cockroach, unable to act and eventually condemned to live as an insect because of his own inertia and indifference. Too little, too late. An anomaly condemned to a meaningless existence. The story of our times?

It was a story that sums up, both in thought, spirit and depiction (literally referring to the cockroach) the arena in which the artist Tazeen Qayyum’s work operates: Narratives can inspire us. Disaster may be immanent but inertia is not an option. Embrace the absurdity of our times with humour, wit and perhaps a bit of entomology. That little tidbit of observation regarding her work is what we come down to much later in the interview though.

A practicing artist for 20 years now, Tazeen graduated from National College of Arts, Lahore, in 1996 with a specialization in Miniature Painting. In 2000 she was awarded a 3-month residency in Vienna, Austria, by UNESCO. The international exposure irrevocably transformed her worldview and Tazeen decided to travel and ultimately relocate to Canada in 2003 with her husband Faisal Anwar, a new media artist.

Affable, easygoing and exuding an all-pervasive air of experience laced with professionalism, Tazeen is more than happy to talk about her initial work and how a love for narratives has remained a constant source of inspiration for her.

“I lived in Islamabad and worked with an NGO that addressed the issue of women trafficking between Pakistan and Bangladesh. They asked me to do a calendar for which I got a chance to review data, statistics, incidents and cases on the subject. This put me on a path where feminist concerns became my mainstay for my initial miniature paintings that had motifs such as the woman in burqa, celebratory wedding garlands of the groom, etc.”

Tazeen is emphatic as she admits that people’s stories do indeed appeal to her. “Conversations are important. What happens around me effects me. I am affected the most by personal stories. Sometimes each painting emerged from each incident.”

Many of Tazeen’s projects have in fact explored the power of storytelling in some capacity whilst touching upon the personal and private. In 2012 she was part of a series of exhibitions titled “Door to Door” curated by Christof Migone for the Blackwood Gallery in Mississauga, Canada, that centered on community engagement through art. In a work titled Threading Encounters, Tazeen volunteered to pluck people’s eyebrows in their homes for a week in return for a cup of tea and conversation about themselves. The objective? “I wanted to play with the idea of displacement whilst keeping the humour alive. By focusing on this supposedly inconsequential concern peculiar to an immigrant of South Asian origin I wanted to invite debate and initiate discourse on larger questions but in a roundabout way.”

As we delve into discussions regarding her various works, the story behind the conception of Our Bodies Our Gardens, an installation exhibited in 2011, also emerges as one such potent point of exploration in which narratives and research forms the backbone of the piece.

“Out of the mélange of my experiences in Canada as a new immigrant, there emerged the familiarity of the water bottle thanks to a very dear friend of mine who used it quite often. It brought back old memories: I had used it as a child, so had my mother and it was a source of comfort. So this ordinary, cheap object which heals and gives comfort became the metaphor for the female body.

I wrote an email to a select group of friends who then forwarded it to some of their select group of friends asking if they used water bottles and if they could send me their stories. In the end 20 stories became the foundation of my work where 50% of the water bottles used in the installation actually belonged to the women themselves. Each bottle represented a story and it wasn’t specific to South Asian women. There were stories from Pakistan, India, the US, amongst others.”

The element of research is quite apparent in Our Bodies Our Gardens but its origin and interest is flaunted in, nay defines her series of works executed in 2009/2010 where the birth of the cockroach as a defining metaphor comes to fruition most effectively. Tazeen introduced the cockroach into her visual vocabulary very early starting in 2002, working and exploring its possibilities yet its beginnings are much more humble than one would presume, embedded in childhood and tinged with humour – and of course we can’t help but share a laugh at the wayward, weird and wonderful ways in which artistic minds work!

“As a Karachite and having grown up in various cantonments, I was never afraid of bugs – in fact I was quite adept at killing them. When pesticide would be poured into the drain, a horde of cockroaches would come pouring out and I guess on some level that image stayed me!”

‘Keeray mukauroaan ki turhaan marna”, quips Tazeen in a matter of fact way. That Urdu phrase became the inspiration for my response to “The War on Terror”. “It’s much easier to look at dead bugs isn’t it? It has become too easy for us to look at death in a matter-of-fact way. It’s all about political propaganda, packaging and presentation. It is sad that we still haven’t learnt from these mistakes made in the past and continue to wage meaningless wars that snuff us out like bugs,” Tazeen continues as she talks about the intricacies, creation and development of the work.

“It was humorous, subtle, and ironic but how do I dig deeper in presenting this bug called a cockroach which is universally considered ugly and detested? What pulled me towards etymology was its systematic execution. I appreciated the pattern, order and grids. So I started mimicking etymological displays of museums which I visited extensively in Canada. I photographed, read, bought tools, kits, a pin collection and even ordered my own labels.”

“Playing with the duality of meanings using pesticide labels such as “Trusted Household Protection”, “Use Full Strength on Difficult Dirt” was very interesting. As for works such as May Contain Scenes of Violence, May Contain Coarse Language, the text is cryptic and deliberately presented in that manner.” Cold, calculated and chilling.

What kind of encounter or experience does Tazeen want the viewer to have when the unpleasant union of the beautiful and the grotesque/ discomfort and humour is presented in the garb of an aesthetic indigenous to this region?

“We have become so immune to rationalizing and naturalizing incidents that it seems much more dangerous than throwing a bomb on some place because people have ceased to simply feel. So I want to consciously make it beautiful, attract the viewer and then bring them to a space of intense discomfort.”

These ideas and this contrast is best explained when one looks at the site specific installation Holding Pattern executed in 2013 at Toronto Pearson International Airport. Created on an invitation by Stuart Keeler, then Director/ Curator of the Art Gallery of Mississauga and Lee Petrie, then curator of the Pearson Airports, flora and ornament in the miniature tradition decorate the flaming red chairs and compete for attention in the same space with the motif of the cockroaches that appear as a pattern being repeated on the wall. “For the people of our region and even me, the airport now signifies a site of paranoia, anxiety and fear of the immigration procedures so the space was appropriate for the content.”

As for the aesthetic Tazeen feels that appreciation would have been quicker and more forthcoming if the Canadian art scene had more awareness about miniature painting. As a South Asian artist one has to contend with the “is it craft?” debate. Fortunately, she has always explored varied mediums of expression. Tazeen is adamant when she says, “work should be judged on its own merit and on what it is trying to say. However the element of labour in art creation is very much alive in the South Asian art psyche and in our region as a whole and we also see a growing trend, a shift in the West of appreciating ‘art making’”.

However, what she is most earnest in wanting to convey and talk about is the relevance of her work in the wake of the rise of populism and the post Trump- election era; pepper that with disturbing narratives that have emerged as a result of what she describes as “a distortion of ideologies” and it becomes food for thought for her. This locus for self-reflection has allowed works such as You Already Knew the Truth and They Walk in His Ways-II to emerge. Her foray into performance and text she attributes to the lofty phrase “We Do Not Know Who We Are Where We Go” borrowed from the work of Italian poet Nanni Balestrini and translated into Urdu. The urge to dabble in this new realm emerged from an Artist Book Project in collaboration with publisher Gervais Jassaud of Collectif Génération, France, where the repetition of this phrase for Tazeen became “the voice for everything I want to say… it resonated with me and I responded”.

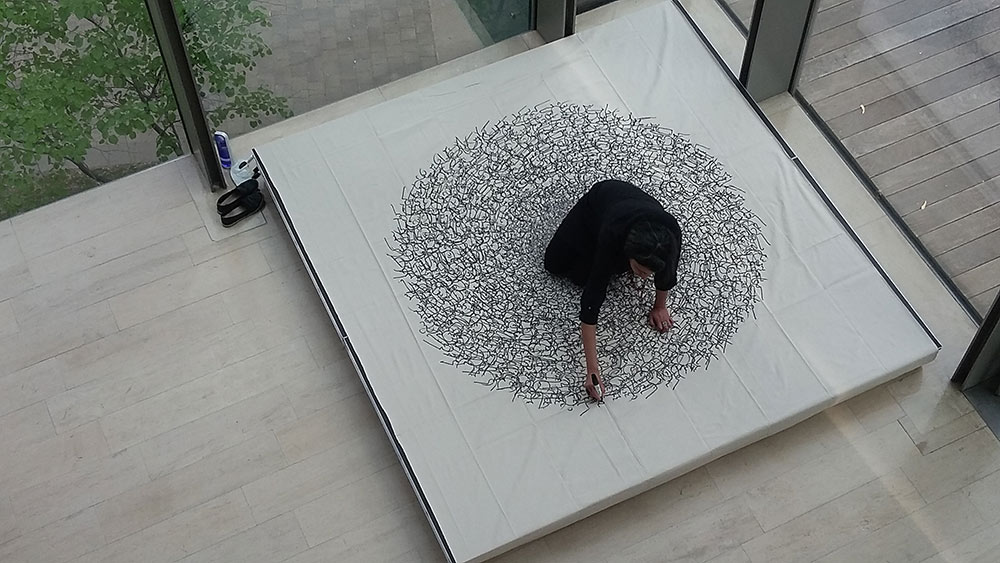

“I wanted to execute my performance on a large scale…so I began writing, repeating the phrase in my free flowing, spontaneous Urdu script. It is interesting that every time that I have used my body for this site specific work, the composition has inevitably ended up taking the form of a circle. I have earphones on as I work; sitting on the floor, standing in front of a wall or glass so I position myself in such a way that I do not see the audience… I have not crossed that barrier as yet where I am truly with the audience.”

Referring to a gallerist who once jokingly asked if her cockroach was a “gora” or a Muslim, Tazeen responded saying “Neither! I’m not looking for a hero or a villain. It has always been the ideologies I have challenged; anything that defies human rights: that is my concern.”

More than anything Tazeen Qayyum emerges as a believer in humanity, passionate and consistent in her convictions.

COMMENTS

Thanks, it is quite informative

This is truly helpful, thanks.