Umaina Khan’s vibrant works explore the disintegration of the human form, highlighting the commodification of women in patriarchal and capitalist soc

Umaina Khan’s vibrant works explore the disintegration of the human form, highlighting the commodification of women in patriarchal and capitalist societies

It would not be out of place to point out that Umaina Khan’s works produce a type of hallucinatory splendor. The exhilaration of flat surfaces covered with irregular blocks of glowing and strident cyans, magenta, and yellow, strategically sculpted with black or chromatic lines, was all the more paradoxical in that their essential content — consciousness housed in the human body itself — was the subject of deterioration or disintegration. To explain further, Khan powerfully interrogated the situation in which attitudes toward women were expressed in commodification and sought to demonstrate how this triggered an alienation of daily life. The human female figure as an inhabited territory was under investigation, and it seemed clear that for Subcontinental aesthetics, the very societal representation, indeed, of female bodily space itself had come to be felt as incompatible with the reality of the body: a kind of vicious aesthetic hegemony far more pronounced than in any earlier era.

Emile Durkheim, a founding figure in sociology, introduced several key concepts to understand social order and disorder, including the theories of anomie and hypernomie. These theories are particularly relevant to women in our societies, when examining on a wider scale, the effects of Capitalism and Patriarchy on society.

Anomie is a condition where social norms are unclear or breaking down, leading to a state of normlessness. Durkheim first introduced this concept in his study of suicide, where he linked anomie to social instability and the breakdown of moral regulation. Anomie arose when there was a significant disruption in the social fabric, such as rapid economic changes, leading to individuals feeling disconnected from the collective conscience and social norms.

In the context of Capitalism, anomie could be understood as a result of the relentless pursuit of economic growth and profit, which often undermined traditional social norms and values. Capitalist economies are characterized by constant change, competition, and innovation, which could disrupt social cohesion and create a sense of uncertainty and instability among individuals. The focus on individual success and material wealth could lead to weakened social bonds, increased feelings of isolation, and a lack of clear moral guidance, all of which contributed to anomic conditions.

Hypernomie refers to a state of excessive regulation and rigid norms, where the individual’s autonomy is severely restricted by overbearing societal rules and expectations. Unlike anomie, where there was a lack of regulation, hypernomie involved too much regulation, stifling individual creativity and freedom. Concerning Patriarchy, hypernomie could manifest through the strict enforcement of gender roles and expectations. Patriarchal societies imposed rigid norms on individuals, particularly women, dictating acceptable behavior, roles, and aspirations. This over-regulation could lead to a suppression of individual identity and autonomy, creating an environment where individuals, especially women, felt constrained and oppressed by societal expectations.

Khan also deployed the visual dynamics of panoramic canvases. Normally, these are particularly well-suited for landscapes and cityscapes. They allow artists to capture the vastness of a scene, emphasizing horizontal elements such as horizons, skylines, or sweeping vistas. Artists could use the extended width to create a sense of progression or movement across the canvas, effectively telling a story or depicting a sequence of events in a single piece.

In the case of Khan, it was the psychological and emotional impact that demanded immersion and engagement. The unusual proportions evoked specific emotional responses. For example, an elongated horizontal canvas could convey a sense of continuity, expansiveness, or even tranquility, depending on the subject matter and execution. Rotated, the narrow coffin-like confines produced restriction and suffocation, simulated baking trays, and thus challenged viewers to think differently about composition, narrative, and their placement in the scheme of things. The works titled Skinny Love and Waiting For A Treat (acrylics on canvas) could be included as examples.

Apart from a strong dose of irony, an accomplished sense of design and composition ran through Khan’s works: The Cake Couple is a large canvas with a broken yellow background out of which two figures – one predominantly in pink and the other in blues – had been sculpted. Almost surely this was a commentary on gendered colour, and the artist had produced a menacing tone in the positioning of the desserts which replaced their heads.

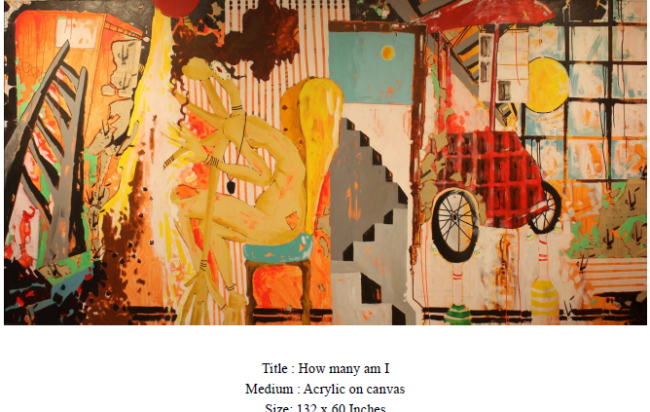

The single work that stood out from the rest in terms of its imagery and technical execution was a large box-like structure titled How Many Am I (acrylic on canvas). It was in fact a processual work apparently completed over a period of four years or so, as per the curator of the exhibition. This work was more reminiscent of a landscape or story-telling picture, with its obvious sectioning, and included some striking examples of experiments with calligraphic Urdu and printed text.

We must turn our attention at this point to the other important aspect of the exhibition, that is, to its curatorial statement as written by Jamal Ashiquain. Ashiquain wrote of “the existence of a person, reduced to a body, wrapped in sweet colorful fondant, presented to be devoured by the men and women who chose to worship and sacrifice their soul to patriarchy.”

Jamal Ashiquain is himself a personage of some standing, being an artist, photographer, performance artist, and archiver in the arts. He is no stranger to discussions and discourse of sexuality and gender in the arts. This writer recalls a significant phase of Ashiquain’s activity, some years ago, in which he was often present as a photographer at art venues, dressed ambiguously in women’s clothing. To most viewers who attend exhibitions with high expectations of immersion in the Arts, or have the notion that a gallery might at least be the one place where art and life meet, this was an exciting and highly satisfying encounter, especially given the virtually reverent ambiance most galleries attempt to surround the art with. Interestingly, this line of investigation, so to speak, turned out to be regarded by some as being too disruptive; indeed an odd reaction in the very locales where such discourse must find support, or else be destroyed and suppressed.

The Artchowk Gallery premises, themselves are expansive and because of being neatly divided into two large show spaces, invite experimentation. Thus, in one section, the exhibition included an unknown performer clad in a traditional ‘shuttlecock’ burqa, wielding a carving knife and offering slices of cake to visitors. Perhaps this demented figure, apparently a stand-in for the artist herself, with a cake embroidered into the headpiece of her burqa, drew only the merest response since one encounters the strangest and most absurd scenarios in the daily run of life here. In the other section, viewers had to contend with a performance collaborator better known as TeeJay, ominously dressed in a pink suit and wearing gloves, handing out wrapped sweets, his eyes enigmatically hidden behind large white-framed sunglasses.

Ashiquain, in a brief conversation during the exhibition opening, with this writer, pointed to the extreme perceptual disjunctions that were the result of the collision of constructs built up in popular media on the one hand, and reality itself. Much could be said about this situation, and in fact the discourse surrounding falsely perceived identities was as old, say, as the invention of television which eventually instituted a regime of the Image.

Luhmann writes: “The selective acquisition of information can only be grasped adequately as an achievement of the system, and that means, as a process internal to the system. The unity of information is the product of a system – in the case of perception, it is internal to the system, as it is of a psychic system, as well as in that of communication of a social system. So one must always clarify which system is making these informational statements.” (Luhmann, Niklas: The Reality of The Mass Media; Stanford University Press.)

Given that, in Pakistan, we are presented with a barrage of information emanating from and controlled by a mass media that is inextricably entwined with our authoritarianism, feudalism, and the machinations of hyper-capitalism, then, however difficult an endeavor it may be, it is just a matter of recognizing the effects and symptoms of the anomie and hypernomie that we have spoken of above, as theorized by Durkheim.

The combination of Umaina Khan and Jamal Ashiquain as two proponents of a discourse on sexuality, gender, and patriarchy then forcefully reminded us of the actual pharmaceutics of our sugar-coated existence, of the societal outer-capsule that must at all costs resist analysis or dissolution to avoid an exposition of sordid truths.”

COMMENTS