The environmentalist Robert Swan once said that the greatest threat to our planet is the belief that someone else will save it. The word of utmost im

The environmentalist Robert Swan once said that the greatest threat to our planet is the belief that someone else will save it. The word of utmost importance here is “our.” With this, suddenly, the planet becomes the responsibility of not one individual, but the society as a whole. The theme for the third edition of Lahore Biennale focuses on Ecology and Sustainable futures.

One of the very important contribution of the Lahore biennale Foundation’s director, Qudsia Rahim was the Collaterals. Curators from Lahore were invited to share their exhibition proposals that resonated with the Biennale’s theme, to be displayed in the city along with the LB03 as collateral events. This ensured that everyone got their fair chance to play their part in saving the planet. With this, we saw more than 20 collateral exhibitions being displayed throughout the city, making Lahore a large living, breathing Art gallery in itself.

Amongst these exhibitions, what stood out was a number of women curators coming forward. In a region where gender disparities have long influenced cultural production, women curators bring fresh insights, promoting a richer and a subtler understanding of contemporary art and culture.

This article reviews the exhibitions displayed by four such curators; Zahra Khan (ArtDivvy), Dr. Sumera Jawad, Fatma Shah and Mariam Hanif

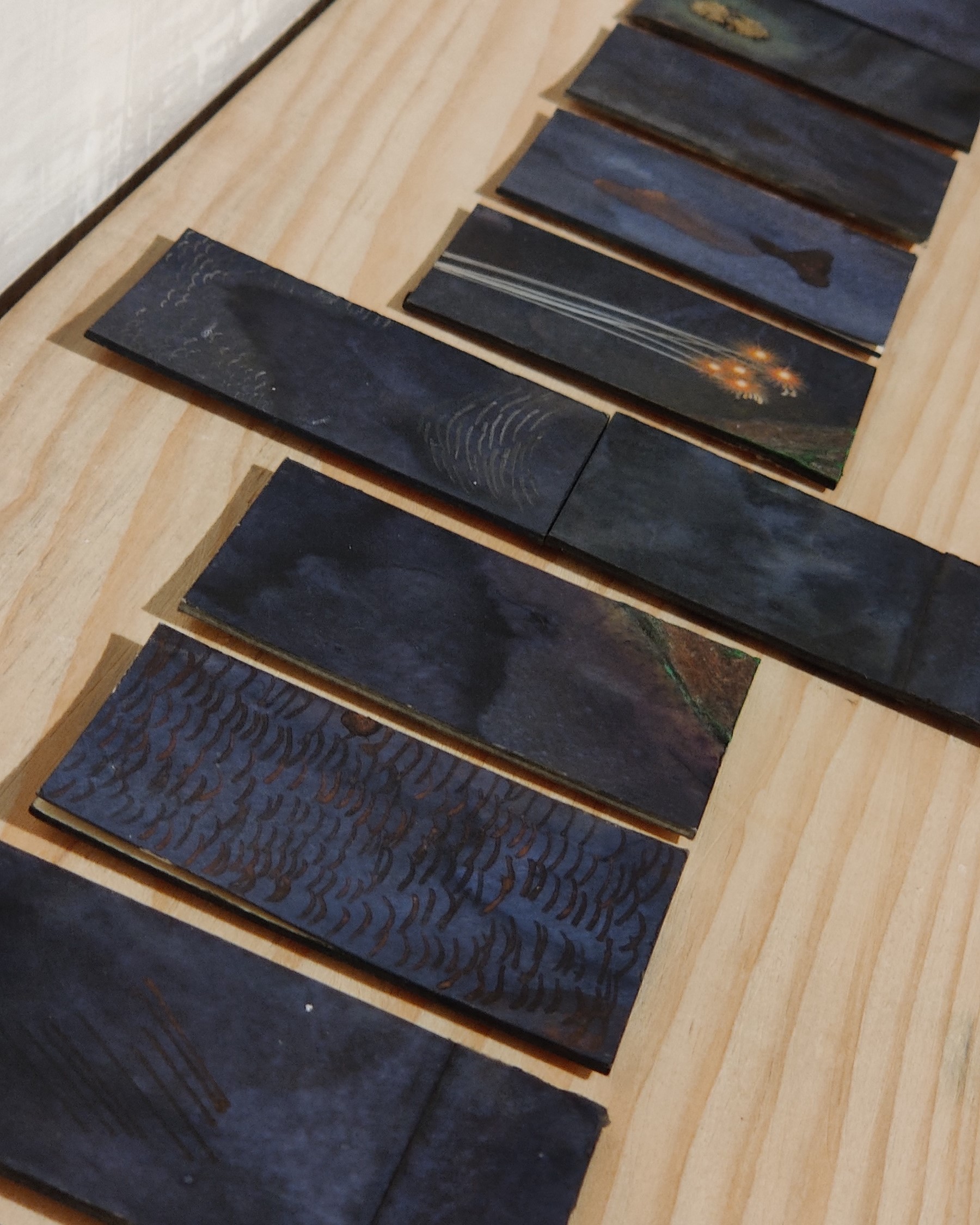

Zahra Khan of the ArtDivy foundation curated a show titled “Knowledge of the Ancients” which explores diverse forms of knowledge, emphasizing indigenous ecological practices, ancient history, and the mythology and mysticism of South Asia. To further align with the exhibition’s theme, Zahra chose a historical building, recently restored by the Walled City of Lahore Authority, that has been in her family for decades. Barkat Ali Islamia Hall’s historic building is associated with the politics of pre-partition Punjab, located on the Circular Road near Mochi Gate. Each of the artist in the exhibition took upon themselves to uncover the forms of knowledge that have been passed down to them. Amongst the artists, Farida Batool studies the intergenerational transmission of indigenous healing knowledge and medicinal plant wisdom, drawing from her grandfather’s practice of hikmat. Bibi Hajra grieves the destruction of an ancient mother tree due to urban expansion, emphasizing the displacement brought on by constant change. Amra Khan addresses themes of genocide and cultural erasure through a sacred altarpiece crafted from a reclaimed window, incorporating symbols from multiple traditions to convey loss and historical memory. Natasha Malik explores themes of gender, sexuality, and memory using Indo-Persian miniature painting, questioning the restrictive narratives surrounding the brown female body. Saba Khan’s work captures the experiences of the Gujjar nomadic community during their migration amid the COVID crisis, drawing attention to their vulnerability in the face of changing borders and social tensions. Mamoona Riaz merges traditional miniature painting techniques with contemporary approaches to examine themes of identity, memory, and the fluid concept of home.

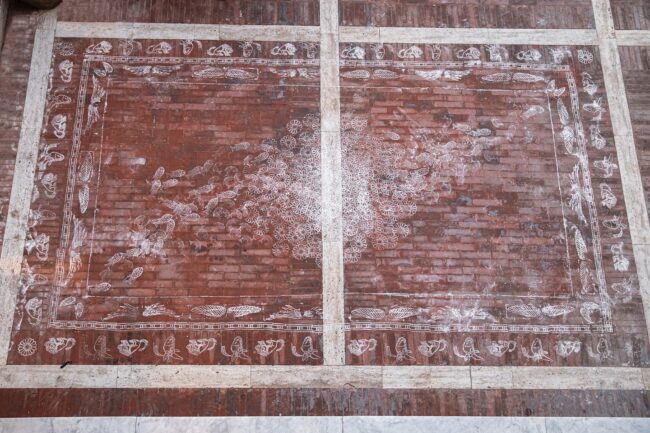

Dr. Sumera Jawad is a seasoned artist and art educator, currently heading the Department of Fine Arts at the Punjab University. Owing to her interest and research on the Gandhara Civilization, she chose to address the theme of the LB03 through the Buddhist environmentalism in her exhibition displayed at PILAC titled “If you exist, I exist.” Each of the artist in this exhibition explored the themes of spiritual ecology and the Buddhist philosophy of interconnectedness. Amongst the artists of this exhibition, Fariha Rashid uses symbolic elements to portray a harmonious coexistence between strength, wisdom, and purity, inviting contemplation on the balance between inner awakening and ecological responsibility. Amina Cheema tries to resolve the conflict between two entities, whether it is man vs environment, man vs man or man vs self. Mona Fazal explores interdependence’s fluid and dynamic nature through the symbolism of a red circle of lights. Nadia Zafar uses the ‘pond’ as a metaphor for our carbon footprint, no longer a tranquil body of water but a symbol of depletion, consuming the finite resources of the natural world. Rabiya Asim’s body of work selectively appropriates and recontextualizes symbols of Gandharan classical art that embodies a confluence of styles and resonates with the ancient material culture. Sumbul Natalia’s installation talks about the importance of the harmonious coexistence of beliefs in a society and how nature and spirituality are universal to all humankind, regardless of our diverse belief systems.

The exhibition titled “Tomorrow isn’t promised” displayed at the Mehta Mansion on 11Temple Road in the old city of Lahore is a curatorial project of Fatma Shah, in which she adopts a comprehensive perspective on our environmental histories, while maintaining an ongoing dialogue on the environment and its fundamental elements—water, air, and land. This exhibition provides insights into various personal experiences and paths, exploring how these narratives may offer lessons in resilience and potential avenues for change, particularly the Gardens. Amongst the artist in this exhibition, Ameer Hamza’s practice reflects the passage of time, tracing the evolution from primitive marks to the scars of modernity, celebrating human creativity while questioning the balance between progress and preservation. Sidra Khawaja aims for a deeper understanding of craft and culinary practices within the conflict zone, its geopolitics, resistance, displacement & ecological exploitation. Maryam Baniasadi’s Tree of Life examine the intricacies of the elements of imagined paradise.

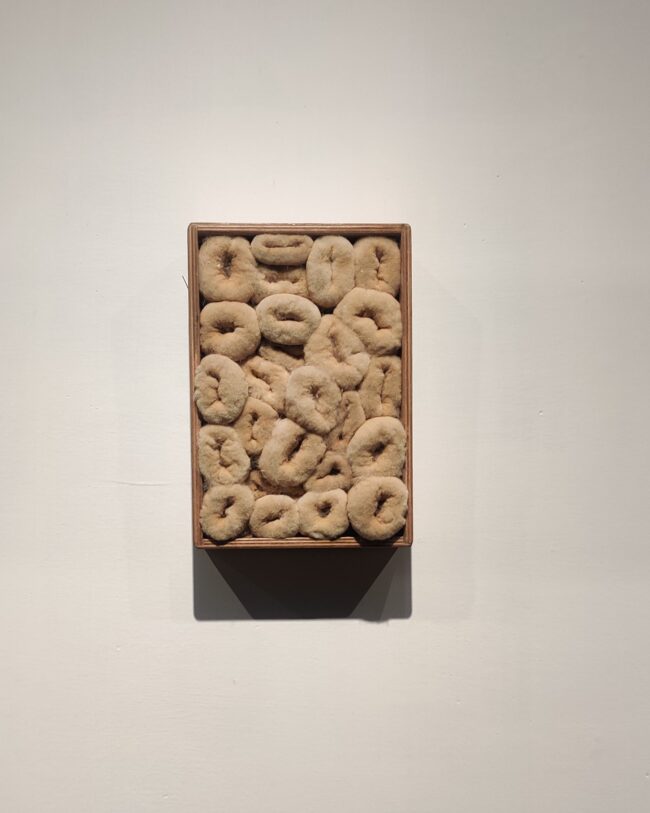

“Past in Bloom – Cultivating Craft in Modern Ecology” curated by Mariam Hanif and displayed at the Artsoch Gallery, talks about the contrasts between traditional practices and contemporary lifestyles. It reflects on the transition from organic, sustainable methods to industrial and consumption-focused approaches, and how this shift has influenced both our environment and daily lives. Whether they be Asad Ali Abid’s delicate sculpture made out of reed grass, or Farrukh Adnan tracing the routes to his ancestral lands trough mapping, or Amna Yaseen’s photograph reinterpreting our understanding of history and the differences that arise across generations, all the artists in this exhibition, emphasize the significance of reverting to sustainable practices, both in art creation and everyday life, to help restore ecological balance.

These collateral exhibitions at Lahore Biennale 03 represent crucial platforms for discourse and investigation, significantly enhancing the primary event by offering varied perspectives on ecology and sustainable futures. The roles of women curators are significant, as they introduce distinctive insights and innovative methodologies for addressing urgent environmental challenges. Their leadership can be seen cultivating a more inclusive and collaborative artistic community. Upon reflecting on this edition of the biennale, it becomes evident that these exhibitions prove to be instrumental in raising collective actions as well as bracing the city with local art alongside the international art displayed as part of the main biennale.