Artist and educationist Seher Naveed’s progressive ability to juxtapose the symbology of structure onto a psychological scheme of urbanity, offer

Artist and educationist Seher Naveed’s progressive ability to juxtapose the symbology of structure onto a psychological scheme of urbanity, offers an editorial perspective of reality that is neither divorced from, nor entirely representative of, the metropolis that is Karachi. Rather, she offers a glimpse into a universe of paradox, where many realities coexist in the framework of a singular three-dimensional space.

In its manifold representations, Karachi is a living, breathing entity, that displays a distinctive tendency to transgress the normative curated model of urban community, hence the title of Naveed’s recent solo exhibition held at Canvas Gallery. ‘Shape Shifting’ is an archetypal foray into the power of the symbol to encapsulate the abstraction of control, power, movement, politics, and even that elusive construct known as performative surveillance, or the hierarchy of state-apparatus in monitoring and filtering data to create a more ‘secure’ environment for the same citizens sacrificing the private, ensuring a measure of safety.

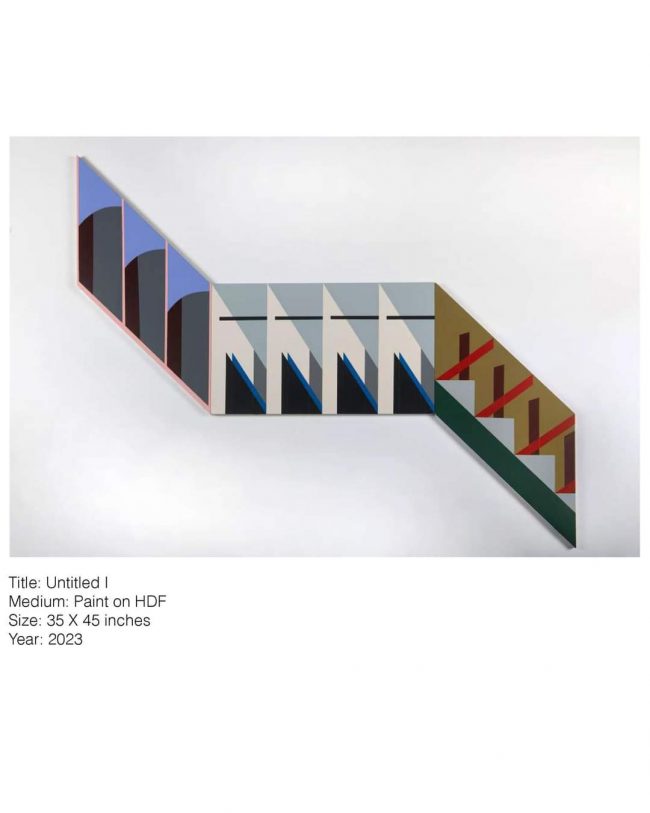

This body of work attunes to the symbology of structure to impose metaphor, abstraction and stratagems to calm the unruly waters of the psyche, yet does so in the language of urban architecture as lyrical, aspirational and soothing while eliciting frissons of future-forward excitement. Geometric modules, clean, minimal lines and the interplay between space, mingle with a refinement and tonal grace creating a dynamic tension that delights the eye. Surveillance culture has gifted us with its unique visual lexicon of man-made geometry, barbed wires, towering boundary walls and gates, where the locus of power lies in the primal line. Naveed recognizes this popular culture capital, and her visual language harks back to the original Abstract Expressionism of the 1950s and later of the 1960s, where creativity hinged on the manipulation of the basic Elements of Art; namely line, shape, colour, texture, space, and value. While doing so, the artist remains devoted to vernacular expression of philosophies of control. From a past exhibition, in which Naveed rendered floor to ceiling gallery walls in the elegant yet sinister colours of containers, the clarity of her devoted expression rests firmly in challenging conceptions of the urban body-politic and its socio-economic ramifications.

Urban security governance is arguably one of the main challenges of contemporary communal management policies, and in the West this will manifest comparatively straightforwardly in the physical realm. However, the South Asian version of security apparatus remains a politically loaded gun, and Naveed is painfully aware of the totemic nature of such constructs. As evidenced by works such as ‘Untitled III’ (Paint on HDF, 24 x 37 inches, 2023), the titular framework suggests an amorphous collection of renderings of the imposing containers that seem to cross the paths of citizens at every juncture, in the face of urban unrest. Be it to control the flow of traffic, quell an angry mob, or create silos for the elite, these building-blocks of power have come to be defined as edifices. Andy Warhol’s repetitive use of the Campbell soup can, or Jasper John’s reworkings of the American flag, both illustrate how re-appropriation of design structures in different cultural contexts, creates entirely new philosophies with which to examine the original symbol.

Undoubtedly, apart from its role as social critic, Pop Art of the turn of the century was the brainchild of a shifting cultural wave – a generation galvanized by the tides of change post World War II. The appreciation of material culture soon followed as a cathartic greasing of the wheels of hyper-consumerism. Yet as this swing of the socioeconomic pendulum made its presence felt across Western living spaces, a loss of individual creative expression was sacrificed. In our own milieu, a similar, yet more insidious wave of ‘fortress mentality’ pervaded the early noughties, as Karachi’s political landscape escalated and a sense of paranoia permeated the atmosphere, soon to become the new normal. Regulating reality through artificial constructs became a necessary evil, as security infrastructure and its tangible manifestations dotted the city. The container thus becomes a stage for civil unrest, while also serving as a reminder of the reclamation of public space by the private. In the collective cultural mind, it then absolves the responsibility of protection by the populace, and by proxy places power in the hands of those who may not have earned it. In ‘Untitled IX’ (Paint on HDF, 36 x 35 Inches, 2023), for instance, the jagged points and coruscating sense of militant hardness of Naveed’s modules, in their repetitive perfection, and of course the two-dimensionality of large swathes of colour, serve as a tongue-in-cheek counterpoint to their actual architectural inspiration. This is Pop Art Nouveau of the Millennial South Asian generation – a cross-hatching of the past, present and future, with a persistently local flavour, yet possessing global appeal in a world rife with the increasing need for physical and non-corporeal demarcations of ‘safety’. What is ‘contained’ here is the cross of sardonic humour nailed to the albatross of a burgeoning population with poor sanitation, devastating unemployment rates, migratory melting pots, crime, severe economic disparities, lack of infrastructure, and corruption, seasoned heavily with desperation.

Naveed’s quiet yet impactful ode to the challenges of maintaining civilization in today’s Karachi, or for that matter any contemporary South Asian megalopolis, maintains that our communal responsibilities require careful re-evaluation on a regular basis. It is not enough to simply cordon off entire communities to protect our fragile sense of independence from the devastation outside ourselves. The moral compass of the future requires us to shape-shift our views on the public and private spheres, and in doing so illustrate the potential for growing equality in the cities we love to be one with. ‘Shape Shifting’ is a clarion call to these complex urban growing pains, and the roles we play in creating them, as well as paving the path to their resolution.

COMMENTS