Preparations for Pakistan’s Independence Day begin almost a month in advance in Karachi. Roadside vendors can be found at every corner of th

Preparations for Pakistan’s Independence Day begin almost a month in advance in Karachi. Roadside vendors can be found at every corner of the city selling all kinds of green and white decorations. Businesses also jump the bandwagon with numerous discounts and deals plastered all over in preparation. When the big day does arrive, nationalism floods our streets with residents sporting the national colours, all cruising the city in merriment.

While many locals expressed themselves with boisterous outbursts, Gandhara Art-Space honoured the day with an intriguing month long group exhibition called, ‘The Past as Present’. Curated by Aziz Sohail, the show exhibited emerging bodies of work from four Pakistani-born artists each of whom use archives to voice out their own concerns. The four oeuvres were particularly chosen and placed in dialogue with each other based on how their practices amalgamated and questioned national narratives through their practice.

Veera Rustomji, a recent graduate, has been focusing on her Parsi heritage and has brought this dissipating culture in the limelight. In this recent exhibition, Rustomji focused on the powerful man, while still keeping in mind her culture. In one corner of the gallery, metal bands were hung at varying levels with wire. These metallic structures are typically used as casts for Gujarati phetas, hats worn by Parsi men, signifying their importance, particularly at favourable occasions. On each hollow piece, colonial images were painted as so to symbolize man’s need to build and conquer. The artist cleverly uses a traditional accessory that is still currently worn by many and in a way has managed to create a dialogue with men of past and present. However, one can’t help but feel a level of empathy exhuming from her work. At another spot of the room, a video, ‘Men Doing Manly Things’ is played where several men are shown performing customarily assumed male activities. The men conform to the expectations of society and perform these activities as if mandatory. One realizes that just as the female suffers societal pressure so also does the male, though the latter may not be as publicly spoken of.

Tackling similar narratives is the work of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. With images of book excerpts printed on cotton twill, Bhutto makes use of his print and newspaper archives. Each print is taken from what seems to be a guide on bodybuilding, written by iconic muscleman, Arnold Schwarzenegger. Each page is home to Western white men but accompanied with an Urdu translation. The amalgamation makes the visual neither Eastern nor Western but attracts the viewer all the same. On top of the big ,strong men soft, floral fabric is sown covering areas of their bare skin. There is the obvious clash of gendered stereotypes happening in each piece but beyond that it can be noted that in the same way cloth is meant to protect and cover the body, so also is this colorful material shielding the men from the audiences’ gaze. Bhutto also makes a comment on the fluidity of gender; there is more to man than just his strength. Rather, to be a complete human being, a soft, gentler side is also important and is nothing to be ridiculed.

Urdu text becomes the focus of Ghulam Muhammad’s work. While not being a native speaker of the language, Muhammad’s practice is concerned with deconstructing and recreating the text until it is much more just another typescript. The viewer can’t help but just stare in admiration at the level of physical skill Muhammad shows through his art. Individual papers of 9’’ by 11’’ were displayed with Urdu text manually carved into each. The negative space of the carving overlap the already printed text making either script difficult to read. In this way the viewer moves beyond their impulse to skim through the words and instead enjoy the form and movement of the alphabet. As part of the display, light was shown through each piece, causing soft shadows through the negative shapes that beautifully blended on the other side.

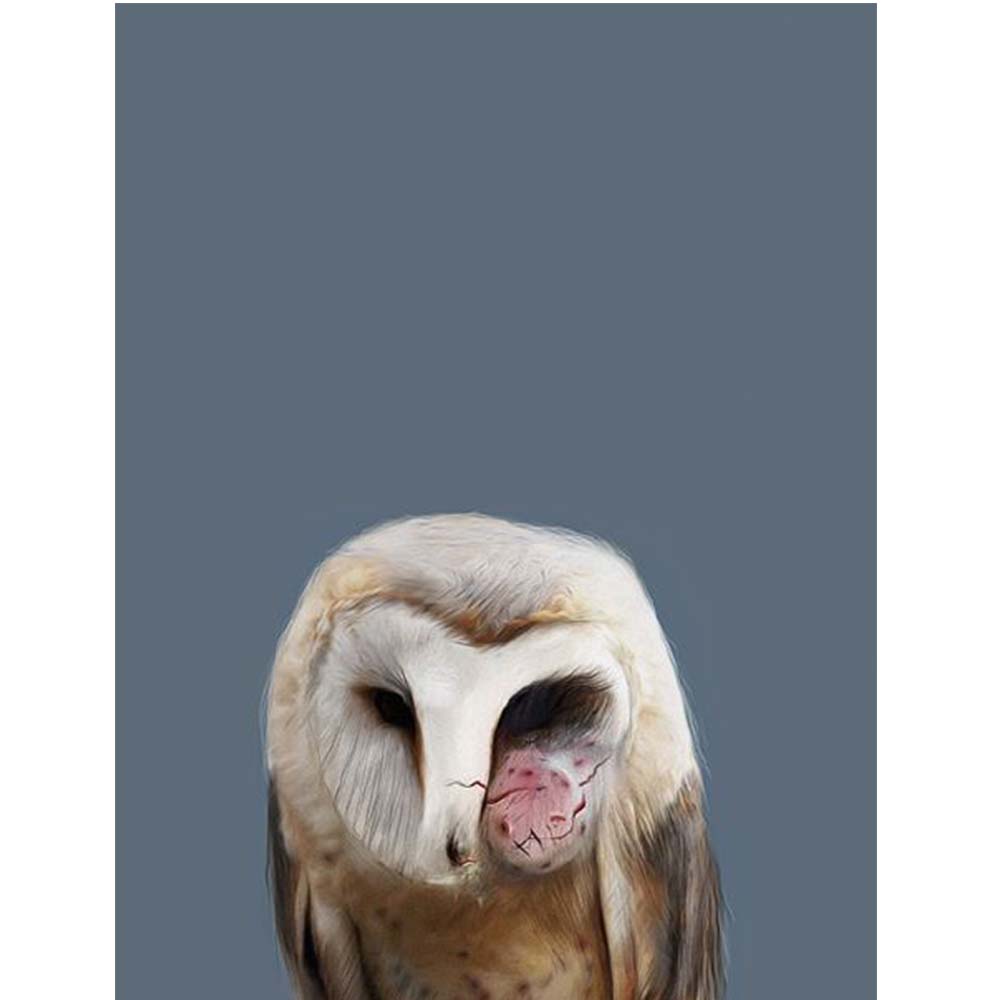

Moonis Ahmed, the final of the four artists, uses memory, archive and fiction in his practice. Using mixed media and light boxes, Ahmed displayed images of fictional birds. All appeared to be injured with blood-red eyed and swollen faces. Two of them hold slabs similar to those held by fresh prison inmates for identification; one of them is even an apparent member of Alcatraz, a once functioning San Francisco prison. The artist is subtle in voicing his concerns by using dark humor through these birds and giving them anthropomorphic qualities. These birds have all done something wrong and now they stand before the viewer exposing the consequences. What is perhaps the most interesting thing in these pieces is the artist use of birds to talk about humanity. Perhaps if people were portrayed with similar punishments one may not have taken as much interest in the work, but because an impossible, almost comical scenario is shown, the work presents a stimulating setup for the viewer and eventually leaves them with an ominous conclusion.

This exhibition celebrates the 70th birth anniversary of Pakistan in a way that may not be ideal for many viewers. Each artist brings forth strong and deep rooted issues which greatly contrast with the lightheartedness many strive for. However, such displays are absolutely paramount in our society. One cannot just go about living in the present without looking at narratives that have brought us there in the first place. Thought-provoking exhibitions such as these must continually be strived for to remind ourselves of what happened so that change is possible.

COMMENTS