The production and reception of contemporary art has in recent years been inextricably bound to ideas of the ‘global’ and concurrently of gl

The production and reception of contemporary art has in recent years been inextricably bound to ideas of the ‘global’ and concurrently of globalization. Located within conditions set by a (post) neoliberal, post colonial, transnational, capitalist world, contemporary art and its considerations must now seek to situate themselves within a ‘global discourse’ that is able to rupture presumptive notions of history and geography as dictated by central (peripheralizing) canons, while maintaining a clear knowledge and ability to navigate between these. As such, the interpretation of art and the theories that come to be employed in such an endeavor must too take on an expanded, if not subversive trajectory, embracing this ‘global turn’ in contemporary art, which defies singular classifications and resists the assignation of a grand narrative to its time, its function, and its discourse. Thus the challenge of critical methodologies in the current time, as set forward by the global-local call of contemporary art itself, becomes the negotiation between the specific (i.e. the local that is culturally rooted and relevant), and the canonical paradigms put forward by a largely western / Euro-American lens through which much of art theory and history has been formulated and written.

Speaking at the broadest level, theories of art seek to address, investigate and analyze the conditions, structures and concepts set forth within artistic projects and processes. In this, primary considerations have found themselves linked inextricably to notions of function and aesthetics, in the compulsion towards a definition of art itself. The 18th century saw the formulation of an autonomous and formalist philosophy of aesthetics, championed by Emanuel Kant, and at the core of which lay issues of art, beauty and philosophy. Amongst other things these would set into motion the colossal discourse on taste, immediacy, desire, ethics, and the beautiful and the sublime. Concerns of aesthetic philosophy could be loosely divided amongst questions of the aesthetic object, judgment, attitudes and experience. While thinkers such as Schelling and Nietzsche sought to establish the position of this field of philosophical study as one of the most critical forms of inquiry, questions of aesthetics would be carried forward even into the 21st century by philosophers such as Danto[1], who in his investigation of the disappearance of beauty as an artistic ideal in the 20th century, would come to disagree with Hegel, Kant and Hume in the construction of a new lens through which to view ideas of the beautiful in art.

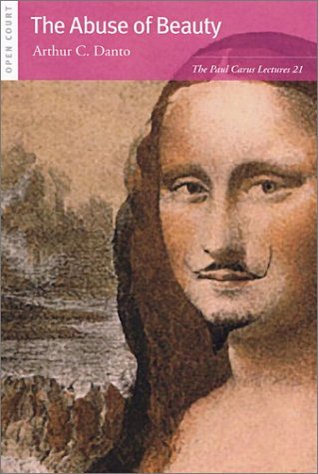

Appropriately, the cover of Danto’s book The Abuse of Beauty (21st ed., 2003) contains the image of Duchamp’s L.H.O.O.Q. (1919), the artist whose urinal (Fountain) two years prior would later come to be seen as the categorical counterexample to definitions of and aesthetic demands on the art object, and instead establish the intent of the artist and the content disseminated within the work, versus notions of ‘originality’ and material formalism, as supreme in the definition of what could and should be defined as ‘art’; Duchamp would in fact refer to works based on formalist aesthetic (surface) qualities as ‘retinal art’. Thus meaning-making, as propounded by Duchamp, would come to define later movements of the 1960s, particularly the conceptual and minimal art movements in the US and Europe, the ‘post-skill’ quality of much of which seemed to signal the ‘death of art’ (at least in the formal aesthetic context, and most certainly in the dismantling of its existing frames of reference).

Of course these movements also stood in response to the deeply formalist Modern Art movement that directly preceded them, with Clement Greenberg as its herald, and which privileged medium specificity and the aesthetic experience as its sovereign principle. ‘Art for art’s sake’, the battle-cry of Modernism, expunged all meaning and representation from the work of art, particularly in the context of painting where Greenberg saw the material qualities of the paint, and the frame of the canvas as the crucial elements of the work, with all else as auxiliary and expendable. However even within this canonical sphere of art criticism and the establishment of theoretical frameworks around this, Greenberg’s views would be opposed by Harold Rosenberg, whose existentialist perspective conceived of the canvas (particularly in the case of the abstract expressionists) as a field of process and action. Where the Greenbergian model situated modernist painting in the linear history of a painting tradition that reached back to Manet, Rosenberg viewed this as a rupture. Nowhere are these contradictory viewpoints more clear perhaps than in Rosenberg’s 1952 essay in Art News titled ‘The American Action Painters’[2], as opposed to Greenberg’s ‘’American Type’ Painting’ for the Partisan Review in 1955[3].

At this point it is apt to return to the 21st century, to the idea of the ‘global turn’ in art and in the frameworks that have historically defined its critical reception and interpretation, particularly in the context of modernism and its prevalent understandings, which recent scholarship and research has served to deeply problematize. Where the canonical models saw Europe and America as the center of artistic activity and scholarship, with all others as a mimicking periphery that occurred as a natural consequence of the former, from which variant formations were derived and could be traced back, these models view the idea of modernism as flexible and unfixed (in time and place), occurring organically and divergently both historically and geographically as a negotiation that lies between ideas of formalism, nationalism, transnationalism, post colonialism, capitalism and globalization. Instead, this is seen rather as a decentralized network of nodes and configurations that reject the reductive and restrictive reading of the western canon. Thinkers such as Partha Mitter argue in fact that in the present day understandings of global modern and contemporary art are no longer possible without the deep consideration of these subjective histories and geographies that exist within an expanded field of alternative modernisms[4].

Thus in the decentralization of frameworks and methodologies, the critique of theories comes to rest in the question of whether any theory of art can truly form a comprehensive and socio-culturally cogent configuration that is able to encompass the complexity of the global and globalized geopolitical realities of a contemporary world. This sentiment is echoed in John Yua’s 2012 study on the work of Hanns Schimansky, which begins with the following thoughts:

“Can any theory about art’s mission be universal? Or is a theory, with its investment in a narrative of progress, more contingent and narrowly focused than the art world is willing to acknowledge […]? Isn’t a widely regarded theory (or vantage point) a sanctioned form of exclusion? An approved way of privileging one thing over another?”[5]

And even within the western canon, it was the injection of knowledge that found its basis in that which lay outside the direct frameworks of art and its narrow, linear art historical methodologies that would fracture ideas of history and society, knowledge and power, and in thus emancipating art, would allow its discourse to extend beyond itself in the creation of an autonomous position not previously accorded to art. Any contemporary and global formulations of critical theories of art must then necessarily seek to look both beyond and within in order to splinter the exclusionary privileging mechanisms that are its own very trap. It is worth understanding here both the narrow and broad readings of what is meant by critical theory today.

In its more specific reading, Critical Theory (in capitals) refers to the moment of the 1930s and 1940s (and beyond through the ‘60s and ‘70s), where the methodological underpinnings of the Frankfurt School and the French anti-humanist movement, as put forward by Adorno, Horkheimer, Marx, Lukács, Benjamin, Althusser, Habermas, Foucault, Badiou, Rancière and so on, would come to locate art squarely within a broader discourse of capitalism and economy, socio-politics, geopolitics, culture, and perhaps most importantly perhaps within ideas of the subject and power, and of knowledge and truth, and the excavation of the archive of history rendered invisible by the dissemination of power by mechanisms of control.

The work of the second generation of Critical Theorists, along with the Continental philosophers and the poststructuralists, particularly individuals such as Deleuze, Derrida and Foucault thus found at the core of their concerns new ways of thinking and seeing and thus of producing and indeed being. In this expanded field of philosophy, these individuals examined, analyzed and deconstructed, caused ruptures and drew linkages between works of literature, art, film in the context of a lived milieu of cultural convergences and divergences and the inevitability of socio-political consequence. It was also through these works, along with Barthes’ meditations, that the rupture of language was enacted, which would lead to the discourse on ideas of translatability – this idea lies perhaps at the root of the problematizing of theory today, and in a larger context in the debate on and critique of the exportation of ‘global systems’ of power and governance in a contemporary world.

Foucault’s project would then perhaps become the most ‘translatable’ of these in its critique of history, knowledge, truth and power, more specifically of mechanisms of power and their constitution, production and reproduction of multiple processes of normalization and behavior, through relations of power and coercive functions that act upon and through bodies – these ideas would become particularly applicable to the late 20th and early 21st century critique of the utopian mission of democracy, in defense of which Rancière would later point out that the lesson idealists must learn from the ‘triumph’ of democracy is that we must put aside the utopian notion of the government of the people by the people for a more realistic, practical point of view; that ‘bringing democracy to another people does not simply mean bringing it the beneficial effects of a constitutional state, elections, and a free press. It also means bringing it disorder.’[6] Although contentious and widely debated, such discourses signal a significant shift in the modalities and methodologies that address the contemporary conditions of society, culture, capitalism, globalization, power and politics, geography and mobility, within all of which contemporary art and its discourses find themselves inextricably bound.

It is also within this that the broader reading of critical theory can be found: a new set of modalities that rejects the given and instead seeks to look beyond – in the context of art, beyond simple aesthetics, reception and interpretation and instead recognizes its rootedness in a broader complex, at once specific and global. Its primary endeavor is rooted in the formation of new ways of seeing, a seeing that is active and critical, that uncovers that which has been rendered invisible to us through these homogenizing forces, a seeing that forces us to face that which is unacceptable or intolerable through showing us not only that which we did not see but also the mechanisms that render us blind to begin with. It rejects and discards ideas of singularity and exclusion, of center and periphery and of hierarchy and privilege, and instead looks towards multiplicities, mobility and movement, the specific and the widespread. It abandons definitions of art itself and in fact embraces the disintegration of boundaries between disciplines such as literature, film, architecture, art, design, and theory. Thus any theory of art today must axiomatically take into account this rejection of classifications, and it is in this perhaps that it sets the greatest challenge not only for itself but also for all practitioners of art, who must now also find their place within this destructured, dematerialized, undelineated and expanded (exploded) field of art thinking and art making – it is exactly in this space between classification and declassification, between the structured and the fluid, that the core of current global contemporary art practice lies.

Zarmeene Shah is an independent curator and critical writer based in Karachi. She currently serves as Head of the Liberal Arts Program at the Indus Valley School of Art & Architecture, and was most recently Curator-at-Large of the inaugural Karachi Biennale 2017.

NOTES:

[1] Arthur C. Danto, The Abuse of Beauty: Aesthetics and the Concept of Art, Open Court, 2003

[2] ‘The American Action Painters’ was republished in Harold Rosenberg’s collection of essays, The Tradition of the New, in 1959

[3] ‘’American-Type’ Painting’ was republished in Clement Greenberg’s collection of essays, Art and Culture, in 1961

[4] Partha Mitter, ‘Decentering Modernism: Art History and Avant-Garde Art from the Periphery’, The Art Bulletin, Vol. 90, Issue 4, 2008

[5] John Yua, ‘What Happens When There is No Center and It Cannot Hold?’, Hyperallergic magazine, October 2012, https://hyperallergic.com/58075/what-happens-when-there-is-no-center-and-it-cannot-hold/, last accessed 24 December 2017

[6] Ranciere, Jacques. ‘From Victorious Democracy to Criminal Democracy’, The Hatred of Democracy, trans. Steve Corcoran, Verso, London, 2006, p. 5

COMMENTS