Artists are the master and art critics and art historians are that disciple. Like me, if you have also spent the new year’s eve in the folds of

Artists are the master and art critics and art historians are that disciple.

Like me, if you have also spent the new year’s eve in the folds of your cosy quilt during the freezing nights of Lahore, you would have not registered the shift in date, nor any changes on the morning of 1st January, from the 31st December, especially with mornings and afternoons in Lahore clad in the dense coats of fog.

As we decipher dates on our calendars, diaries, notebooks, watches, mobiles, we also know that time moves without these demarcations/descriptions. Diverse communities follow separate calendar systems, i.e., Gregorian, Hebrew, Islamic, Bakrami, Chinese, Zoroastrian, etc: All human inventions. Likewise when we divide art into years, or even decades, we are aware that these are pure assumptions. Not different from classifying art on the basis of nation-states. Particularly in reference to countries, which were carved/created out of a larger tract of land. Like Pakistan, or countries which were segments of Yugoslavia, or republics from the former Soviet Union.

Identification through a country could suffice some complications. Today we proudly proclaim A. R. Chughati and Ustad Allah Bux were the great/first masters of Pakistani art, but a substantial number of their earlier paintings were produced in undivided India. In fact Chughtai was considered an important Indian artist prior to the Partition; and so was Ustad Allah Bux who worked for various princely states before 1947, and same was the case with Haji Muhmmad Sharif, the celebrated master of miniature art.

One can claim that what these artists made after the creation of Pakistan is Pakistani art, and all that came before may not be classified as such. But making an oil painting, producing a watercolour with several laborious and time-consuming washes, and executing a miniature painting require days, weeks, even months. So what would be the case, if for example A. R. Chughtai, Ustad Allah Bux, or Haji Muhammad Sharif had started one of their paintings, say in the first week of August 1947, and were only able to complete it on the 28th of August, or 5th September of that turbulent year. In what national category that particular work would fall. Work, whose earlier part was rendered as an Indian artist (hence part of the Indian Art) and later half was done as a Pakistani painter (one doubts even if these masters were thinking or even bothered about this matter/split).

Same is the case with authors. The great novelist and short story writer, Qurratulain Hyder moved from India to Pakistan, published her landmark novel, Aag ka Darya (1959, Lahore) before returning back to India as its citizen. A few artists also began their careers in India, and later opted for Pakistan, and earned their name, place, and respect in the Islamic Republic or vice versa, like Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, who migrated to India.

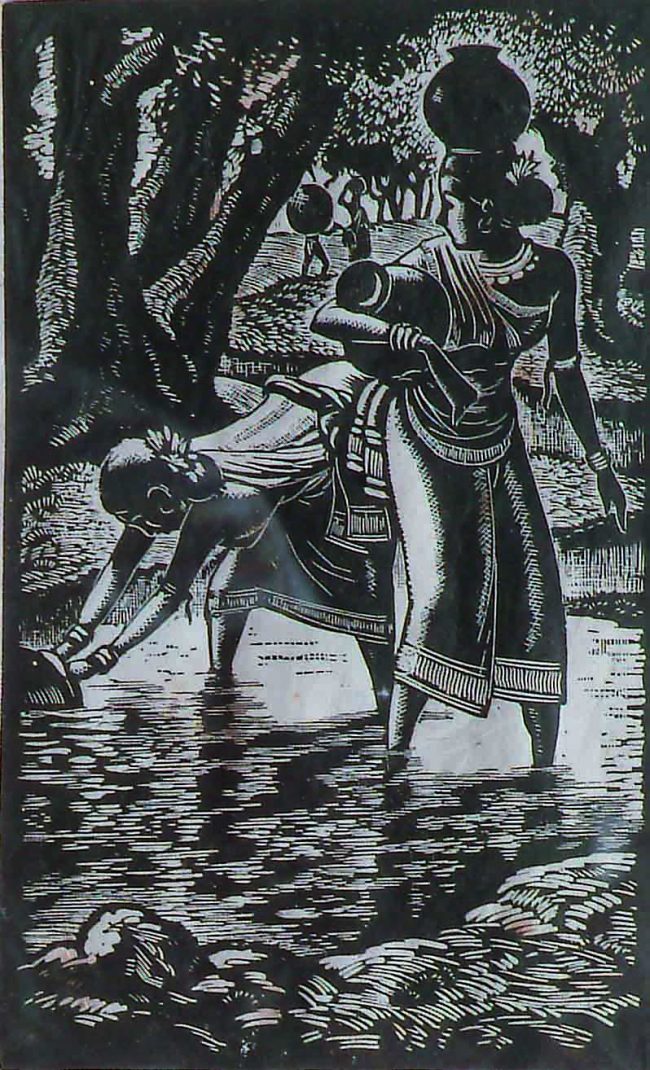

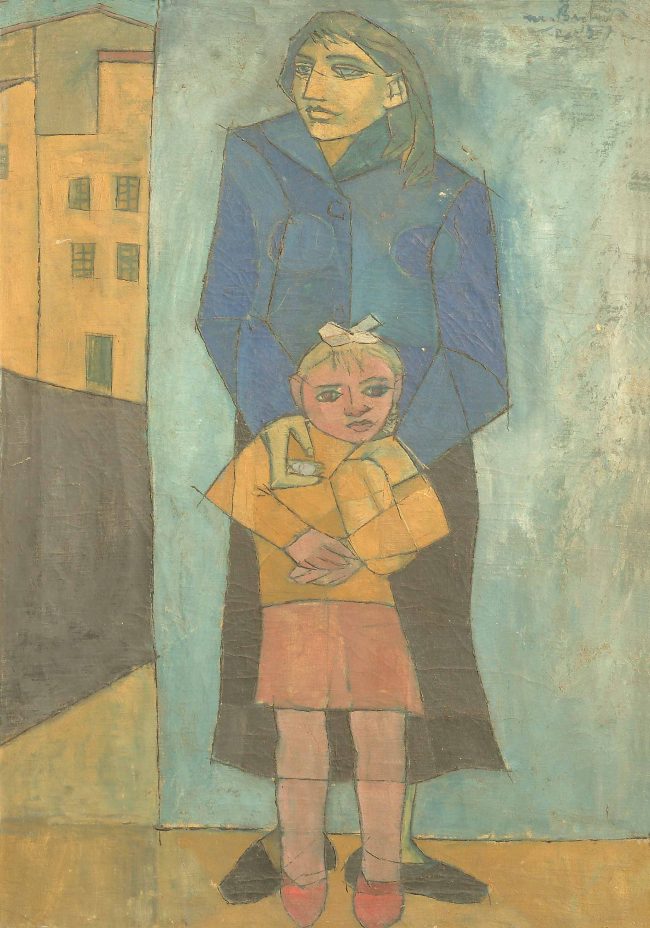

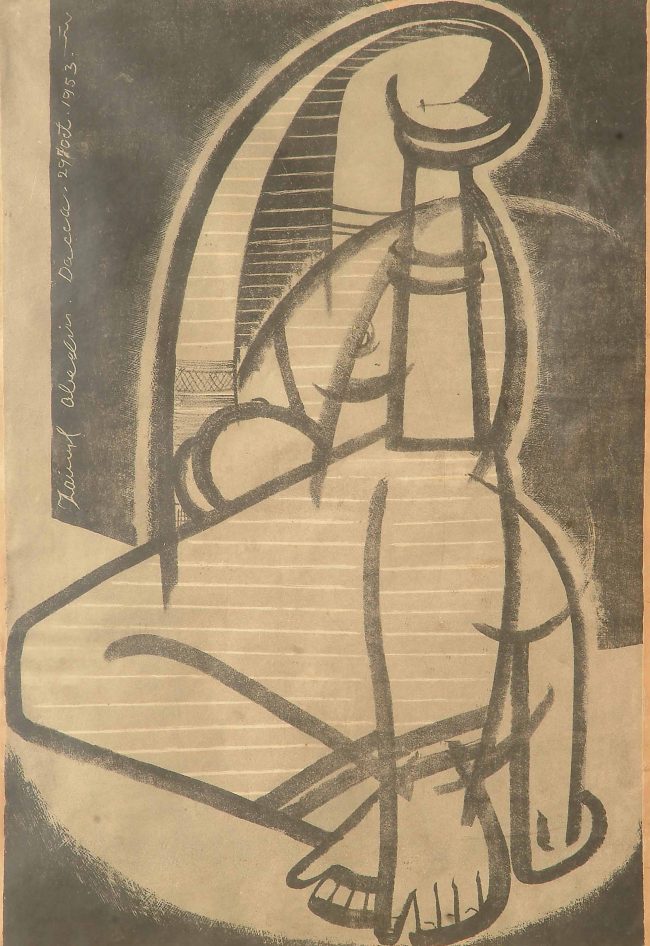

The divide does not stop here. Because before the former East Pakistan earned its independence as Bangladesh in 1971, several Bangla artists were part of Pakistani art. They participated in exhibitions held in Karachi and Lahore, their works are still displayed in Pakistani’s National Art Gallery (Islamabad) and in the collections of Lahore Museum, Alhamra Art Museum, and Karachi Arts Council. They are mentioned in the books on Pakistani art, like Art in Pakistan by Jalal Uddin Ahmed (1954), and Paining in Pakistan, by Ijaz ul Hassan (1991).

One presumes they are also part of Bangladesh’s art, yet the question is where to place certain works of Zainul Abedin, Safiuddin Ahmed, Murtaja Baseer, Novera Ahmed, Aminul Islam, which are included in the history and publications of Pakistani art. One can extend this issue about the blurring of boundaries and the diffusing of national identities. David Alesworth, an English artist, after enjoying a considerable level of recognition in the UK, decided to move to Karachi. He settled, worked, exhibited and taught (and influenced generations of young Pakistani artists) in Pakistan. Won prizes of Sculpture at the National Exhibitions held in Islamabad. After spending many years in Pakistan is now living in the UK, where he makes art, and mostly participates in Pakistan-related exhibitions or in solo and group shows in Pakistan. His case can be compared to V. S. Naipaul, the descendant of indentured labour which were brought from India to Caribbean islands. In one of his books, the Noble Laureate informs how in West Indian Trinidad, he was regarded as the Indian, while in India, he was seen as the West Indian, and in the UK he is recognized as the West Indian-Indian!

People travel from one place to another, or their parents migrate, or their grandfathers/grandmothers settle at distant lands; or their ancestors have originated in faraway, unknown and unconnected regions. But before the DNA test becomes a norm, or a fashion, we have surnames of Pakistani artists, such as Bukhari, Gilani, Madani, Tirmizi, Bilgrami, indicating their links to cities in Iran, Saudi Arabia, India and the Central Asia. The history of their ancestors’ travel to this territory is long, and in many cases ambiguous.

When there are such complexities in terms of chronology of an artist’s origin, similarly it is not justified to judge an artwork on the basis of when it was conceived, researched, fabricated, and exhibited. As an artist, one knows that a single work is like one among a family of numerous offspring. Each with a unique identity, character, habits, tastes, yet shares some features of his/her siblings, or parents or even with close relatives. So if an artwork is created in 2023, it may have started 25 years ago (like a mixed media collage of Iqbal Geoffrey that is dated 1982-2007), or probably further back – or the week before. So the date inscribed on the work, or mentioned in the caption details does not make much sense, or relevance to determine the newness of an artwork.

In that context, the general routine of re-viewing a past year in terms of literature, visual arts, cinema, music, theatre is unreal. Because a movie screened in 2023, may have started in 2019, was complete in 2021, got the Censor Board approval in the last month of 2022, and after negotiating with the distributor finally showing in the cinema halls in January 2023. A book that was published in 2023, was actually finished in 2021 by the author, later it was edited, proof-read, and then the stage of gallows, till it came out in the market in February 2023, just to coincide with some literary festival. A theatre production takes years to stage, like a music album to get it released, so labelling these pieces with a specific year could be misleading.

As erroneous as evaluating an author or a painter on his/her last book, or the latest exhibition. If the novel is published now, one is sure that the writer is already well advanced into his/her new book. And if an artist’s exhibition is happening recently, he/she may have been busy in the studio dealing with new works. So dates and chronology, or for that instance, history in the context of creative practices, are arbitrary. On the works of art from the past – no matter from the East or the West, or from the North or the South, no dates were inscribed.

Yet we still cling to and yearn for dates, months, years. When was a work of art created, when exhibited, when collected etc. While in front of an artwork, we are like the disciple of a Buddhist monk, who was accompanying his master on a long journey. Before crossing a bridge a young woman met the two and asked if one of them could carry her on his shoulders to drop on the land. The master took the responsibility till he reached the other side. Both the pupil and the master continued walking, and after many miles the disciple questioned the monk, ‘master we are not supposed to be in touch with the females, but how come you transported a woman on your shoulders for the entire length of the bridge?’ The monk replied, ‘Oh I left her a long time ago, but it seems you are still carrying her’.

COMMENTS